Imagine a late-night scene: Restaurants, bars, revellers, and a lit-up sign advertising a hostelry. Is this modern Shanghai? Hong Kong? Vancouver? Las Vegas? Actually, such scenes were already taking place a thousand years earlier. Emily Zhou reports.

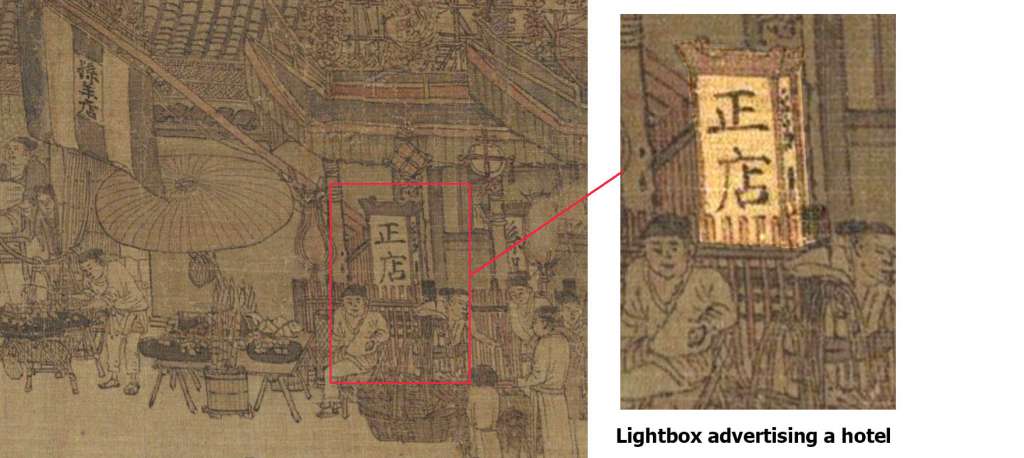

AN ANCIENT PIECE OF ART shows a lightbox advertising a hotel: perhaps the earliest evidence of a light-powered advertising sign in history. In other parts of the same image, shown further below, we see large gardenia-shaped lanterns, indicating that these restaurants were busy in the evenings.

The pictures above and further below are extracts from the Chinese masterpiece “Along the River During the Qingming Festival”, which we have mentioned before: see this link.

It is a huge mural showing multiple scenes, and a key source for historians to learn about Chinese society in the past. The picture provides details of many busy crossroads, where people managing various business can be found.

For much of China’s history, the authorities were quite strict about merchants and restaurateurs. Day-time business areas and night-time residential areas were segregated, and storefronts were not allowed to spill over into the streets. But the evidence from this portion of this five-meter long scroll shows that an urban revolution had begun in the 11th century.

City dwellers had begun to enjoy what we would now call “night life”.

STRICT RULES

For much of China history, the authorities insisted that people followed strict building rules known as the “Square City System” (坊市制). Before and after the three-century period known as the Song Dynasty, which lasted from 960 to 1279, activities had to take place within walls which divided the whole urban area into prim squares.

Although the Song was preceded by the famous Tang Dynasty, which lasted from 618 to 907, and was known for running a relatively tolerant, open and cosmopolitan society in Chinese history, town planners still followed the rules of square city system.

Chang’an, the capital of the Tang empire, was a square of complete axial symmetry with Rosefinch Avenue (朱雀大街) as its central axis. Residential areas and business districts were separated by straight walls, making the city like a geometric chessboard.

Apart from the two squares of the East and West Markets, all the other areas were forbidden to people who were running businesses. Furthermore, the government set opening and closing hours, to remind citizens to go home in good time. This meant that if residents wanted to go shopping, they must follow the schedules of opening hours for each district.

Things changed in Song Dynasty, a period of more economic freedom. The walls were demolished because of eagerness for commercial development from the rulers and the people.

If we look (above) at the design of Kaifeng (開封), the capital of the Song empire, sharp lines for cutting society into prim squares have disappeared. The edges of the city have become irregular and soft. Not only are the walls skewed in order to cater to the demands of residents’ dwellings, but the streets were no longer sharp, straight lines.

There were small streets and alleys going in various directions. Even Bian River Avenue (汴河大街), the main street, was shaped naturally according to the coastal outline of River Bian (汴河) flowing through the whole city. Clear boundaries between residential and commercial areas no longer existed. Merchants expanded their booths and stores onto the streets, more closely interacting with customers. To encourage commercial development, the rulers took a hands-off attitude. As long as businesses paid their taxes, they were allowed freedom to run as they wished.

ORIGIN OF CHINA’S NIGHT LIFE

The general nine-hour curfew of the Tang Dynasty, where people were expected to be at home during the evening and all night, was relaxed to a four-hour period between 11 pm and 3 am.

That meant people did not have to go to bed early. What effect did that have on the streets at night? How did people react when the metaphorical and physical walls of the city districts collapsed?

They went out in the evenings – and the concept of “night life” was born.

For convenience of citizens walking at night, gardenia-shaped lamps made from red yarn were very popular on the streets. Looking at the evidence of the artwork “Along the River During the Qingming Festival”, we can see that large, showy lamps were placed side by side with the sign advertising the presence of a hotel (see below). Both the lamps and the signs were hollow boxes containing candles.

It’s hard for us to imagine exactly how bright the streets were a thousand years ago. But a description in a book called “Tittle-Tattle of the TieweiHill” (鐵圍山叢談) written by Cai Tao (蔡絛) in Song Dynasty may help:

“On midsummer nights, the whole country suffers from mosquitoes and flies, but there is no bother on Maxing Street in the capital. The candles in the light boxes burn from dusk to curfew, and the smell from the burned candles in the downtown district effectively dispels mosquitoes and flies.”

Cai Tao

That helps us imagine the scene in medieval China. People were “hanging out” on streets during evenings that were as bright as daytime.

Curiously, it may be that the people during this relaxed period may have had more fun than the ruler. That’s the evidence of a famous story about Emperor Renzong of Song (宋仁宗).

One night, the Emperor was in his palace when he heard sounds outside. He stood up and moved to the window. He could hear music and laughter.

He called a servant and asked: “Where does the sound come from?”

“It is the music performed in restaurants and markets, your Majesty,” the servant replied. “The outside world is so lively these days that it makes your palace seem quieter than it used to be.”

The Emperor thought about this. Maybe the person at the top has to suffer loneliness, so his people have the freedom to party – for if the leader spent his days partying, then it would be the people who would be lonely and suffering.

The ruler had stumbled on a great truth. For happiness, you don’t need a palace and great wealth. Instead, you can spend a pleasant evening chatting with friends over good food and drink at an open-air restaurant. Even today, it’s hard to think of anything better.

Some images above come from the book 風雅宋:看得見的大宋文明, written by Wu Gou (吳鉤). Image at the top by ZHENG XIN on Unsplash