The world’s media reported that at exactly midnight on 30 June 1997, the British Hong Kong flag was replaced with China’s flag as the sovereignty of Hong Kong moved from British colonial rule to Chinese rule. But that’s not actually what happened. Emily Zhou reports.

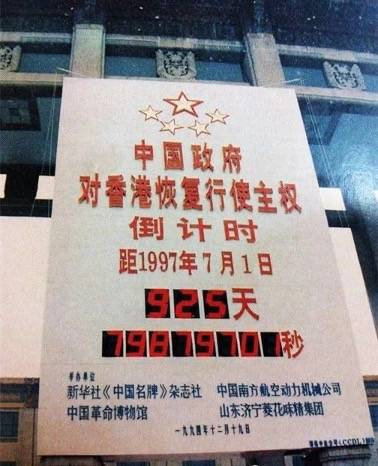

IN THE WINTER of 1994, 925 days before July 1, 1997, a countdown board appeared in Tiananmen Square (天安門廣場) in Beijing. It counted down the days, hours and seconds before Hong Kong’s change of sovereignty.

In the next 925 days, almost everyone who visited the square took a photo in front of the countdown board.

The event of course was poignant from the Chinese point of view. Although the Chinese had always continued to officially see Hong Kong as part of their country (a segment of Bao’an County in the province of Guangdong), the west’s “gunboat diplomacy” meant that they had effectively lost control of it to colonial conquerors.

AN OCCUPATIONAL HAZARD

Quick history: It had been more than a century and a half earlier, on January 26, 1841, that a British Expeditionary Force planted the Union flag on Hong Kong Island for the first time. At the time it was technically an illegal invasion and occupation, for there was no agreement of any kind until the infamous “unequal treaty” was signed in August of that year.

How long did the colonial rule last?

From that time until July 1, 1997, when China’s red five-star flag would rise in Hong Kong, 156 years, five months and four days would pass. The British Empire came from the sea and would now retreat from whence they came.

MR AN’S QUIBBLE

It was a momentous occasion, so you would think that it would be scripted right down to the second or milli-second.

So it seemed in the period running up to that fateful day. But a man named An Wenbin (安文彬), chief director of the ceremony on the Chinese side, spotted a problem.

There had been a series of 16 meetings between the Chinese and British governments. During the last negotiation, Hugh Davis, the British negotiator, quoted from the 1984 Sino-British Joint Declaration that Britain would hand over Hong Kong on the 1 July 1997, but noted that it didn’t specify the time. He insisted that the British flag would be lowered at precisely midnight 0:00:00, when June 30 became July 1.

But Mr An took issue with that. He calculated that it would take two seconds for the music conductor to lift his baton and strike the beat, signifying the first note of the playing of the Chinese national anthem—and the raising of the Chinese flag.

If the playing of the first note and the action of beginning to raise the flag needed to happen at exactly 00.00, the British side would have to finish earlier, and the Chinese side would have to have an extra second or two.

An said: “To raise the Chinese flag precisely at midnight is our bottom line. That one second means the end to you but the beginning to us. Ever since the founding of the PRC, even during the most difficult times, we have ensured to protect and respect British rights in Hong Kong. But this year is different. It’s already been 154 years, and Hong Kong is finally returning to China. We won’t, and we can’t wait one more second.”

The British negotiator resisted at first, but Mr An was resolute – and he had a good point. The British had humiliated China by taking its land through a show of force. Giving up a second or two was not unreasonable. He conceded. The Chinese conductor could have two or three seconds of the British colonial timeline to lift his baton and mark the opening note.

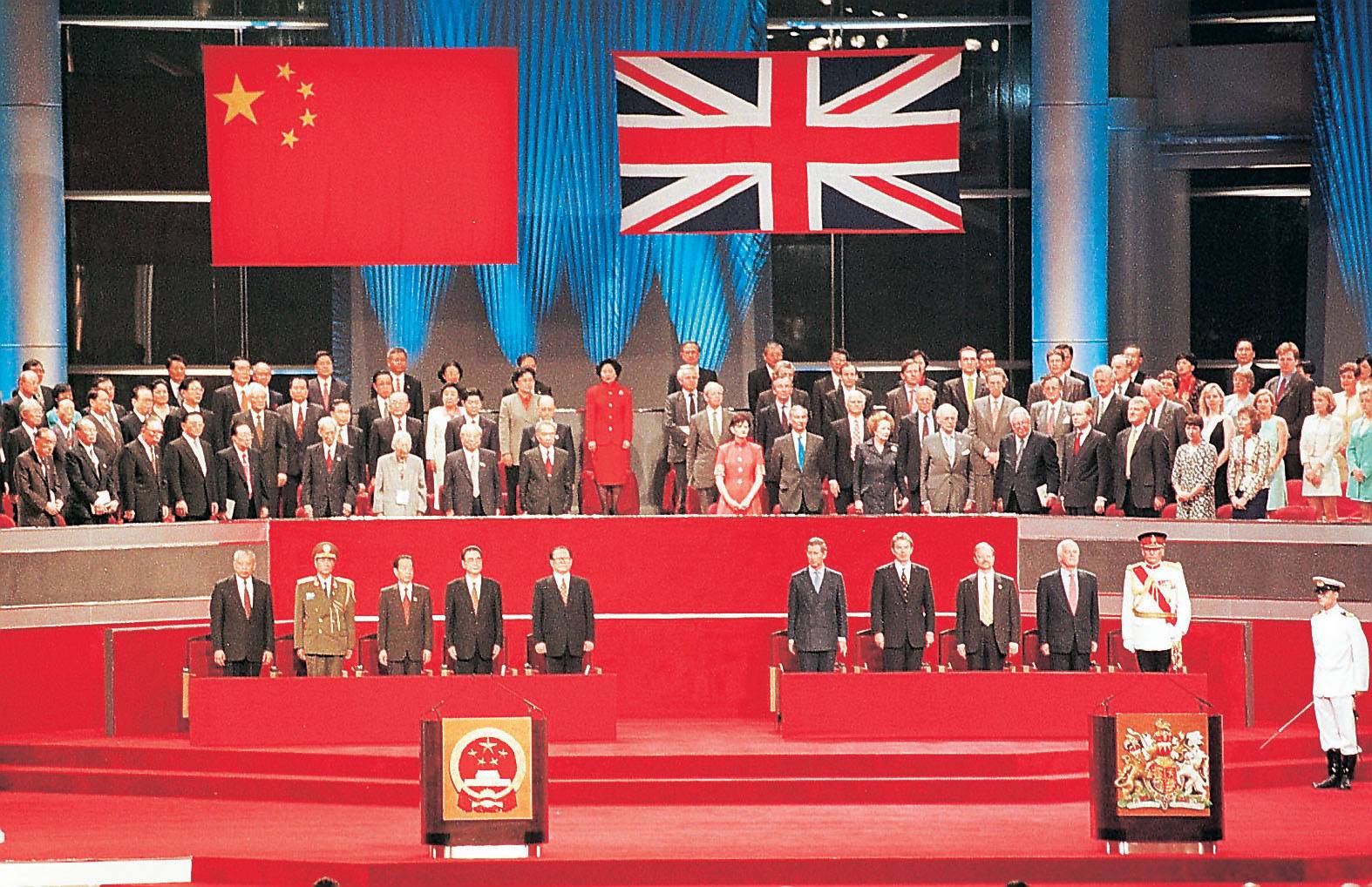

The agreement was made. The British flag would not be lowered at midnight. Instead, it would be lowered by 11:59 and 57 seconds on June 30, 1997.

But when the evening rolled around, the British timing was imprecise. At the crucial moment, the British flag came down about 12 seconds early, instead of two seconds early. There was a pause. Several seconds passed. Prince Charles was puzzled and looked up and around.

“What’s going on?”

There was a puzzling silence in the room as everyone waited for something happen. The empire was over. Britain had lowered its flag. Colonial rule was done.

But nothing was replacing it.

The Chinese side was determined to get it right, having rehearsed it to the millisecond. They waited. Nothing was going to rush them.

Ten seconds passed. Then was heard the trumpet note that begins the Chinese national anthem. The music started at midnight, and the Chinese flag raiser, a man named Zhu Tao (朱濤), smoothly raised the flag. At precisely 00.00 Hong Kong was welcomed back to Chinese sovereignty, after ten seconds in limbo.

Flag-raiser Tao was a character. He had reportedly practiced 5,000 times to sync precisely with the playing of the anthem. Just before the handover ceremony, he felt his nose would bleed, so he stuffed two cotton balls up his nostrils. Sure enough his nose did start to bleed and he had to swallow the blood, making it hard to breathe at the crucial moment. None of these details emerged until later.

However, the Hong Kong media immediately decided he was a “super handsome man”—and started writing about him. He also got the job as flag-raiser for the return of Macau two years later.

Meanwhile, the Hong Kong Police had all been given replacement badges for their caps, and immediately switched the colonial one for the national emblem of China.

It was, by any reckoning, a fascinating moment in history. Of course, the press has long had a tendency to demonize China, so many people were expecting disaster. But the handover instead had ushered in a surprising lack of change. The “one country, two systems” policy, which its mixture of structure and flexibility, worked well.

And as Mr An and the British negotiators had seen, a mixture of structure and flexibility is usually the best recipe to make things work smoothly.

This article includes material from this Chinese language site and this site. Image at the top from Cottonbro/ Pexels