An ultra-simple magistracy-level case in which the facts were not in dispute was blown up into a years-long string of high level hearings by the improper injection of headline-friendly concepts from the west.

Below, top legal commentator Henry Litton looks back at a notorious lawsuit which illustrates how Hong Kong’s legal sector has been infected by cases driven by western concepts that don’t serve the community – but make tabloid-friendly headlines and win big fees for lawyers.

This is the third of three parts on related topics, but can be read independently. To read the first part, click this line. To read the second, click here. To read an earlier essay by the same author, outlining the topic, click this line.

HAS THE HONG KONG JUDICIARY LOST ITS WAY? Make up your own mind after reading this cautionary tale from the Magistrate’s Court.

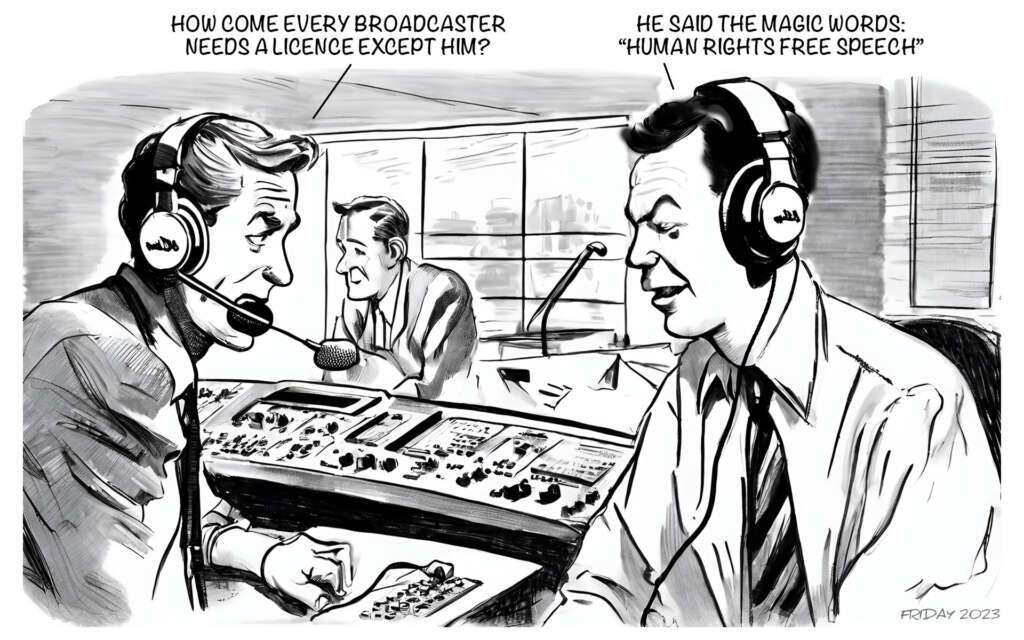

The human rights industry feasts on cant, confusion and obscurity.

In retrospect, it can be seen how, in the early days, the courts themselves prepared the banqueting hall, and Legal Aid stood as servers at the table.

Take Secretary for Justice v Ocean Technology & 6 Others [HCMA 173/2008; 12/12/2008]. It started life as a straight forward prosecution in a magistrate’s court: a court of summary jurisdiction.If there ever were a simple case, this would be it. Yet it generated a Court of Appeal judgment of 24 pages, full of citation of overseas “authorities”.

The case concerned the setting up of what was called “Citizens Radio”.

The radio spectrum is a limited resource, shared amongst civilized communities on earth. It is controlled by the International Telecommunication Union which allocates part of the spectrum to member countries, of which China is one. China in turn allocated part of its entitlement to Hong Kong. There are multiple uses of the spectrum including the police, fire and ambulance services, the Civil Aviation Department, etc.

In Hong Kong, the radio spectrum is regulated by the Telecommunications Ordinance, Cap.106.

Section 8 says: “Save under and in accordance with a licence granted by the Chief Executive in Council ….no person shall: (a) establish or maintain any means of telecommunication or (b) possess or use any apparatus for radio communication …”.

Section 20 stipulates that anyone who contravenes s.8 commits an offence punishable by a substantial fine and imprisonment.

There cannot be a simpler regulatory regime than this.

In open defiance of the law, the defendants set up transmitting systems in various places, operating what they called a Citizens Radio, transmitting on FM frequency. They had no licence to do so.

TOTAL NONSENSE

When brought before a magistrate on charges under s. 8, the facts were not in dispute. The proof of guilt was overwhelming. But the magistrate acquitted them on the ground that the regime of control under the Ordinance was “unconstitutional” for infringing articles in the Basic Law and the Bill of Rights guaranteeing the right of free speech.

This was total nonsense. The magistrate’s own constitutional role under the Magistrates Ordinance was to determine the matters as charged. His jurisdiction was confined within the four corners of the charge sheet.

He had no right to adjudge the constitutionality of statutes legally enacted by the legislature and determined as part of the laws of the Region by the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress. On the charges facing the magistrate, neither the Basic Law nor the Bill of Rights was engaged. He was operating outside the law. Not surprisingly, the Secretary for Justice appealed.

The only true issue before the court was whether the defendants operated radio transmission systems without a licence, as to which there could only be one answer: Yes. Conviction under s.8 necessarily followed.

The appeal went before a single judge, as the Magistrates Ordinance required. One look at the papers should have convinced the judge that the appeal must be allowed, and the matter sent back to the magistracy to determine the guilt or innocence of the defendants according to law: that is to say, the Telecommunications Ordinance.

But no. Counsel had raised a “constitutionality” issue; the court must kowtow to counsel. The matter was therefore transferred to the Court of Appeal, elevating a simple matter of law enforcement into a sumptuous banquet for human rights lawyers.

The offences were committed between July 2005 and October 2006. The Court of Appeal gave judgment in December 2008: more than three years from the time of the first offence.

The court’s leading judgment was given by a Justice of Appeal whose name, to avoid embarrassment, will be omitted.

At para 63 the Justice of Appeal said:

“We were treated to an extensive examination of authorities which have addressed the issue whether (and, if so, to what extent) a defendant might raise as a defence to a criminal charge the validity of a decision taken pursuant to the statutory authority or whether he was consigned instead to running such an issue in proceedings for judicial review”.

What on earth does this mean?

The answer seems to lie partly in para 5 where he said:

“The key question raised by this appeal is whether the constitutionality of the statutory licencing regime prescribed by the Telecommunications Ordinance has any bearing on the constitutionality of the offence-creating provisions”.

This was not the key question of the case before the magistrate, now under appeal. The key question was whether the defendants were guilty or not as charged.

The question formulated by the judge in para 5 was an artificiality created by counsel: a multi-headed monster: (a) whether sections 8 and 20 of the Ordinance were “constitutional” (b) whether the Ordinance itself creating the regime of control over the use of the radio spectrum was “constitutional” and (c) whether sections 8 and 20 were “free-standing”.

None of these were matters properly before the magistrate.

The case, from simple law-enforcement, was turned into a cause celebre.

Given the complexity of the question raised, it is not surprising that the rest of the judgment descended into virtual incomprehensibility.

Take para 65 where the judge said:

“……the charges were not founded on a failure to comply with a licensing regime …..What was at issue …..was whether the respondent company had a broadcasting licence and, if not, whether the offence-creating provision was itself unconstitutional and impermissibly infringing a protected right”.

Infringing “a protected right”, said the Justice of Appeal. What could that be? Surely not a right to broadcast without a licence. A “right” then to obtain a licence?

IT WAS ABSURD

That, on its face, is absurd. You have no more right to a driving licence than to a broadcasting licence. But it set the judge off on a chase through multiple overseas “authorities” – including the First Amendment to the US Constitution – and concluding in para 69:

“It must follow that no person has a right to a broadcasting licence”.

He continued in para 70:

“Given that the requirement for a broadcasting licence is a permissible fetter on the freedom of expression, and that there is no right to a licence, it is difficult to see, in the context of the magistrate’s remit to determine the charges of establishing or otherwise operating means of telecommunication without a licence, and of the specific legislation under consideration, upon what basis it was relevant for him to determine whether the discretion of the Chief Executive in Council to grant or refuse a licence was prescribed by law”.

What more was needed to allow the Secretary for Justice’s appeal?

Astonishingly, there followed 16 long paragraphs where the judge examined overseas cases where “the legality of an administrative decision might properly fall for determination of a magistrate in criminal proceedings” (para71 ).

This was a pure academic exercise which led nowhere – except to lengthen the judgment and bring in more obscurity.

The rest of the Court of Appeal ( which included the Chief Justice ) concurred with the judgment. The Secretary for Justice’s appeal was allowed. The magistrate’s dismissal of the charges was set aside, and the case remitted to the magistrate’s court for resumption of the trial in accordance with law ( para 116 ).

What message was sent to the legal profession by the way the matter was handled in the Court of Appeal? That the rule of law required discipline, brevity and focus on real issues? Or that cant and prolixity were acceptable?

And looking at the matter more broadly, did it not, yet once again, give oxygen to those bent on mining the system in purported vindication of human rights?

The Honorable Henry Litton was Permanent Judge of the Court of Final Appeal in Hong Kong from 1997 to 2000.