“Human Rights” sounds like such a worthy, positive concept. But it has been used to poison the Hong Kong legal system, says former judge Henry Litton, one of the most widely respected legal minds in common law.

THE HUMAN RIGHTS INDUSTRY found its first roots in 1991 when the Hong Kong Bills of Rights Ordinance was enacted, based on the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR): a treaty subscribed to by over 100 countries, as diverse as Iceland, Turkey and Japan. Many of the norms and values are endemic in the Common Law system, such as the presumption of innocence in the Criminal Law.

If looked at sensibly and proportionately, the Bill of Rights was no big deal. But some lawyers saw it as a new game in town and jumped on the bandwagon with glee. Since then, it has grown and corrupted the culture of the legal system, making of the legal process a slow lumbering confused monster, bloated with wasted words and ultimately subverting the principle of “One Country, Two Systems” which mandates the opposite: the clear vigorous and effective implementation of the Hong Kong system.

PROBLEMS SOON AROSE

The first test came in the case called the Queen v Sin Yau Ming, September 1991, before the promulgation of the Basic Law.

In the fight against serious crime, situations may arise where, once certain facts are proved, the likelihood of a serious crime having been committed is such that the burden shifts to the Defendant to explain his innocence.

Take a luxury villa in the New Territories registered in the name of a BVI company where the apparent owner has the front door key. Inside is found a big cache of heroin (白粉). It is unlikely it’s there for his own consumption. A statutory presumption under Section 46(d) of the Dangerous Drugs Ordinance then arises, that he is not merely in possession for his own use but that such possession was for the purpose of trafficking in Dangerous Drugs – a much more serious offence.

The bar for the presumption to arise in Section 46(d) is low. Herein lies a problem. Now, the chemical name for heroin is salts of esters of morphine, that is the consumable heroin. But in the same section there is esters of morphine, generally known as heroin-base, not consumable, but which after another process becomes heroin. The bar for the presumption of possession for the purpose of trafficking in the two instances is identical. Both are very low.

That makes no sense. If you are found in possession of a small of amount of heroin, that most likely is for personal consumption; but if you are found in possession of the same amount of heroin-base, the likelihood is that you are involved in manufacturing and trafficking in Dangerous Drugs.

In short, as a matter of common sense and fairness, the bar to the presumption of possession for the purpose of trafficking to arise should greatly differ in the two cases. In the case of mere possession of heroin, the bar for the presumption of trafficking to arise should be much higher. To that extent, that part of Section 46(d) is structurally defective and should be struck down, to be replaced by a higher bar.

INVASION OF WESTERN ABSURDITIES

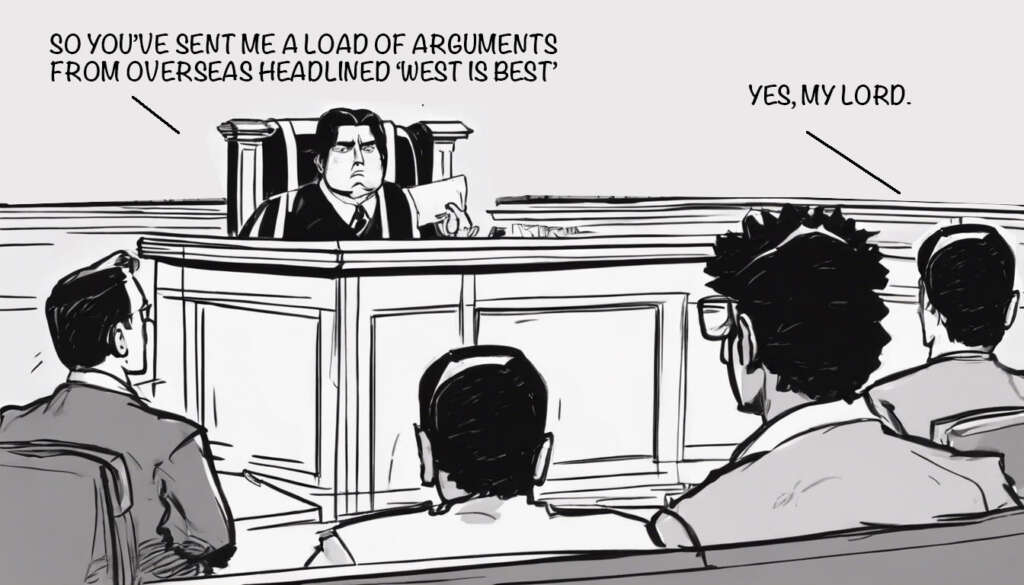

Those essentially were the facts in the Queen v Sin Yau Ming. Instead of approaching the presumption of innocence in Article 11-1 of the Bill of Rights and applying it to Section 46(d) of the Dangerous Drugs Ordinance in that sensible way, the Court was led by Counsel to take onboard jurisprudence from Europe, Canada and the USA. This clogged the judgment with indigestible polemics and led nowhere except to confusion. And thus the monster began to grow.

The profession totally ignored the cautionary words of Lord Woolf in the Queen v Lee Kwong Kut where he said “…it must not be forgotten that decisions in other jurisdictions are persuasive and not binding authority and that the situation in those jurisdictions may not necessarily be identical to that of Hong Kong. This is particularly true in the case of decisions of the European Court of Human Rights.”

He went on to say “…Normally, by examining the substance of the statutory provision which is alleged to have been repealed by the Hong Kong Bill of Rights, it will be possible to come to a firm conclusion as to whether the provision has been repealed or not without too much difficulty and without going through the Canadian process of reasoning”.

Lee Kwong Kut was one of the last cases decided in the Privy Council.

HUMAN RIGHTS WEAPONIZED

Since then human rights have been weaponised to subvert the Basic Law, using the Court as platform for political and ideological causes.

The tool for this was simple and effective: to load onto the Hong Kong judicial system the massive overbearing weight of Eurocentric jurisprudence: European directives on human rights, determinations of the Grand Chamber of the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg etc., all these transplanted as Hong Kong domestic law.

Thus, the legal system was subverted.

BREATHTAKING ARROGANCE

Take the notorious face covering case decided by two High Court judges in November 2019, at the height of the insurgency, a case said by the Hong Kong Macau Office of the State Council as a “blatant challenge to the authority of the NPCSC and to the power vested in the Chief Executive by law to government”.

In a 100-page judgment beyond the comprehension of man or beast, the Court roundly proclaimed that the Emergency Regulations Ordinance was “not compatible with the Constitutional Order laid down by the Basic Law”.

The arrogance of this approach is breath-taking.

‘TOTAL NONSENSE’

Take another example: the attack on the “831 Decision”: the ruling made by the NPCSC on August 31, 2014 regarding the composition of LegCo in 2016 and the Chief Executive Selection process in 2017.

Prior to this there was public consultation by the government and reports and recommendations by the Chief Executive to Beijing in relation to those matters. These came under attack by agitators, heavily funded by Legal Aid.

Take the case of Kwok Cheuk Kin v Chief Executive of HKSAR and the Government of HKSAR, a judgment delivered by Au J. in May 2017, on an application ex-parte for leave to start proceedings for judicial review. The relief sought by Kwok was an order to “quash” the Chief Executive’s reports and recommendations to Beijing.

It was total nonsense. The Chief Executive was accountable for the governance of Hong Kong to the Central Government, not to a High Court Judge in Hong Kong.

APPLICATION TO START

Martin Lee SC with Kent TC Lee appeared for Kwok, instructed by the firm in which Albert Ho Chun Yan was a senior partner, supported by Legal Aid. Martin Lee SC put forward four supposed grounds for impeaching the Chief Executive’s actions. They were, again, total nonsense.

What was before the judge was a mere application for leave to start proceedings, where Kwok had to persuade the judge in Chambers (not in open court) that he had standing to bring the proceedings, and had a viable case for relief. This was a matter between Kwok and the judge alone, without the putative respondents – the Chief Executive and the “Government of the HKSAR” – being vexed. One look at the papers should have convinced the judge it was total nonsense.

But there they were: Benjamin Yu SC, Abraham Chan, Eva Sit for the Chief Executive appearing in open court before the judge. If discipline of law were maintained and the rules of court observed this is what Senior Counsel for the Chief Executive should have said:

“I should not be here. My client the Chief Executive should not be here, Judge, represented by me and my two juniors. Order 53 Rule 3 of the High Court Rules requires you to determine the application for leave ex-parte. Mr. Lee’s arguments are total nonsense. You can see that for yourself. He is playing games with the judicial process and with the Basic Law. I decline to participate in such games. The Chief Executive will not participate in such games. I as counsel will not take part in an abuse of process. That is all I have to say. To do more debases the rule of law and demeans the constitutional role of my client the Chief Executive”.

Then he would have sat down.

That is not what happened.

POLITICAL THEATRE

The perhaps most troubling aspect of the matter is this: Counsel for the Chief Executive made submissions in response to Martin Lee SC’s arguments. They debated on whether the proceedings were “academic”, and so-called authorities were cited on both sides, meeting rubbish with rubbish, and demeaning academia in the process. The absurdity of the proceedings was disguised by the flummery, the bowing and scraping, the “my lord”-this “my lord”-that.

The judge, having chewed over the arguments, delivered a so-called “Judgment” of 17 pages, dismissing Kwok’s application for leave to start proceedings. And in his last paragraph the judge said this:

“…finally I would also like to thank counsels for their assistance in this matter.”

Assistance.

Here the essence of the matter is revealed. Kwok failed in his application, but Martin Lee SC had won in spectacular fashion. He had successfully converted the Court of Law into a political platform where his piece of theatre was so engaging that the judge, in the full glare of the footlights, had thanked him for it.

U.S. POLITICIANS

Martin Lee was founder of the Democratic Party. He and other leading “democrats” were, at that time, strutting the world stage, having photo opportunities taken with leading US politicians like Nancy Pelosi. One of them even made it onto the front cover of Time magazine.

Martin Lee is also a prominent barrister. He heads the Bar List. It would demean his standing as a lawyer to suggest that he didn’t know perfectly well that Kwok had not the ghost of a case for relief against the Chief Executive. The object was not to win the case for Kwok but to make the Judiciary an ally in his political cause, to air grievance over the 831 Decision of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress in open court.

And in this he had succeeded triumphantly. The judge did not say how many of his supporters were in court to share in his glory. Martin Lee and his team must have left the court room chuckling behind the judge’s back.

PARTIES PLAYING GAMES

This case was not an isolated instance. One wonders how a case like this could have got Legal Aid and by what process counsel was assigned? How much of taxpayer money has been expended on cases like this? Was there no assessment of merits by lawyers in the Legal Aid Department?

When a case of this nature gets to open court it diminishes the rule of law; it gives oxygen to parties playing games with the judicial process and the Basic Law. It has a trickledown effect on society as a whole. By slow degree, the fabric of the law unravels as the human rights industry fattens. It encourages indiscipline and thuggish misconduct, leading to elected legislative councilors making mock of oath-taking before assuming office; it gives agency to unruly conduct in the Legislative Councils’ chamber.

Since that time the legal system has become a bloated lumbering monster, unable to bear its own weight, clogged with indigestion.

Is this the full vigorous and faithful implementation of the overriding principle of One Country Two Systems, a principle that governs everything else in Hong Kong?

A further article by the same author on this topic can be read by clicking this link.

The Honorable Henry Litton was Permanent Judge of the Court of Final Appeal in Hong Kong from 1997 to 2000.