IT WAS ARGUABLY the most mismatched war in history. The British invaded the Chinese state of Tibet in 1903, leading to the deaths of an estimated 2,700 Tibetans.

And just five British officers.

This extraordinary story has three main elements:

First, the presence of a western superpower, known for its unmatched weaponry, acting provocatively to secure its sphere of influence, far from home.

Second, the circulation of rumors about threats: In particular, a tale that Russian invaders were planning to invade multiple countries and had to be stopped, and that China was quietly working as Russia’s partner.

And third, the existence of a country positioned in-between these powers: one which was very poor and not officially at war with anyone.

The description above sounds like it could refer to events in Europe today.

But in fact, the exact same elements describe a forgotten battle that took place just over a century ago.

This is the extraordinary story of the British “expedition” to Tibet.

By Emily Zhou and Nury Vittachi

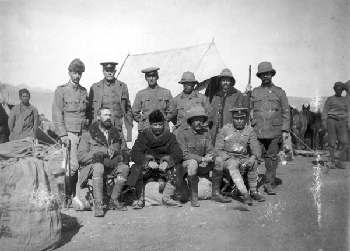

IN AUGUST 1903, General Francis Younghusband led a party of British officers, and a large support unit of soldiers from British India, towards Tibet, which was at the time a state governed by China under a deal struck in 1720.

They spent about three months setting up and positioning the “expedition” at the Chinese borders. Then they waited for an excuse to move into Tibet. Why?

General Younghusband had come to believe that Russia had a large secret military presence in Tibet, and was planning an invasion to sweep across multiple borders, snatching Tibet from the Chinese and taking India away from the British. World domination was the plan. The contest was called “the Great Game”.

He had two pieces of evidence: one was the presence of a Russian monk named Argvan Dijiev in the Dalai Lama’s group of senior supporters, and another was the sighting of cluster of Russian rifles in Tibet.

The General wanted to head off the Russians and invade Tibet himself, taking at least part of it from Chinese rule to British rule—as they had done with Hong Kong, on the other side of the same country.

PROVOKING AN ATTACK

But he needed an excuse to justify crossing the border, so he repeatedly tried to provoke the Chinese protectorate into a confrontation, according to Duel in the Snows, a detailed record of the invasion by historian Charles Allen.

But the army struggled to get the violent response they wanted.

Then, in December, the British heard about some tension in the area, with Tibetans trespassing into Nepal. This was not technically part of India, but could be viewed as a de facto protectorate of the British.

Younghusband interpreted this as an act of Tibetan hostility against the British, and claimed the moral right to cross into Chinese territory.

It was later shown that the incident was small and had been misrepresented. Some Nepalese yaks and their drovers had trespassed into Tibet, and the locals had driven them back.

THE INVASION BEGINS

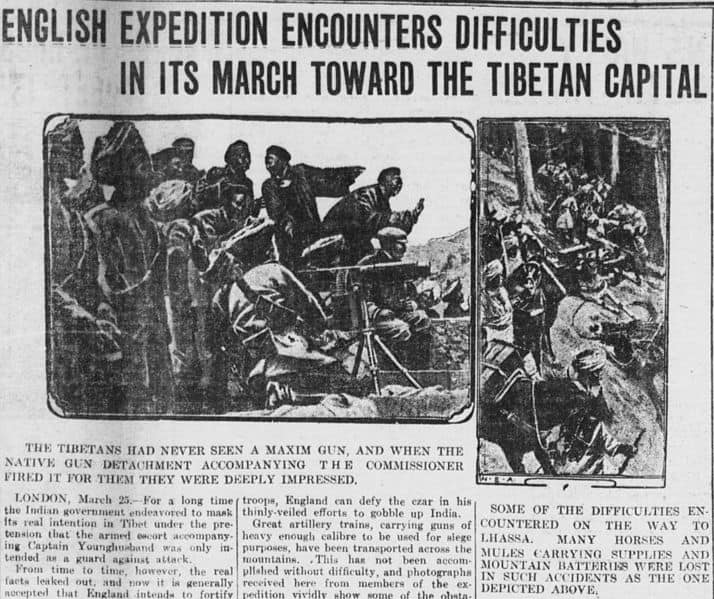

But by then the invasion had started. The heavily armed British party moved into Tibet on December 12, 1903. The 3,000 fighting men were armed with two Maxim machine guns and four pieces of heavy artillery. Literally thousands of workers followed to service the troops, and there were several thousand mules and yaks to carry food and weapons.

The British army included many Gurkhas and Sikhs, who had experience at fighting at high terrains, where the air was thinner.

General Younghusband, anxious to present the British as heroes, was intent on presenting the invasion as the fault of the Russians.

BLAMING THE VICTIMS

But Lord Curzon, British Viceroy of India, told him to downplay the concerns about the Russian monk and the rifles, and blame it entirely on Tibetans violating the peaceful British frontier.

“Remember that in the eyes of Her Majesty’s Government, we are advancing not because of [monk] Dorjyev, or Russian rifles in Lhasa, but because of our Convention shamelessly violated, our frontier trespassed upon, our subjects arrested, our mission flouted, our representations ignored,” Curzon wrote. The tone must be one of British outrage against the behavior of people in the Chinese territory.

When the British encountered Tibetan leaders, they insisted that this was not an invasion – although this was plainly untrue: armies don’t march into other countries bristling with weapons. One reporter was happy to share the real reason for the invasion in one of his dispatches, printed in a British newspaper: “England can defy the [Russian] czar in his thinly-veiled efforts to gobble up India.” (The cutting is printed further down in this report.)

But how unbalanced was this fight going to be? Historian Charles Allen said: “It was a clash between the mightiest political power in the world and the weakest.”

SLAUGHTER

The situation became tense, and in open ground near a village called Guru, fighting broke out, with British accounts saying that a Tibetan fired the first shot after arguing with a Sikh from the invading army.

The British had advanced weaponry and a highly trained army. The Tibetans had primitive muskets, handmade swords, plus bows and arrows, knives, and herding whips. Most of the Tibetan “soldiers” were peasants, shepherds, or monks, pressed into service.

It was no contest—just wholesale slaughter. In a short space of time (one witness said four minutes), hundreds of Tibetans lay dead.

The remainder turned to flee.

“Bag” as many as you can, the British commanders said, using a hunting term for killing. Soldiers shot the retreating Tibetans in the back, although at least one eventually lowered his rifle. “I got so sick of the slaughter that I ceased fire, though the general’s order was to make as big a bag as possible,” wrote Lieutenant Arthur Hadow, commander of the Maxim guns detachment. “I hope I shall never again have to shoot down men walking away.”

At least 700 Tibetans died in what became known as the Massacre of Chumik Shenko. The result was a bloody river winding down the snowy mountain range. And that was the prelude to what some call the War of Gyantse.

A SHORT WAR

Two more battles followed, the first at Red Idol Gorge, again easily won by the British. The final stand for the locals was at a high level rock fort at Gyantse. With British superiority in weapons, strategy and combat, the Tibetans quickly lost the final fight too.

Where were the troops from Chinese heartland? Technically, Tibet had become part of China some two hundred years earlier, and should have been protected. The power system since 1727 was that China’s Imperial Commissioner-Resident of Tibet would grant official seals and certifications to the local religious and political governor known as the Dalai (達賴).

CHINESE WEAKNESS

However, the First Opium War in 1840 had shown that the Chinese philosophy of focusing inward was no longer tenable in a world where expansionist military powers were operating by a might-is-right policy.

The Qing Dynasty Chinese simply did not have the strength to protect Tibet.

During this period, the Dalai Lama fled to Outer Mongolia, while a Qing Dynasty commander named Youtai tried to negotiate peacefully with the British – at once stage, even offering food and drink to the invaders. In contrast, the Tibetan army had run out of food, swallowing snow to stave off hunger and thirst.

General Younghusband, meanwhile, was thrilled with the way his army won every battle.

Historians estimate that between 2,000 and 3,000 Tibetans lost their lives. Army records show that just five British officers lost their lives in combat, plus 29 “native” (ie, non-white) soldiers. Other lives were lost through illness, accidents and other circumstances.

UNEQUAL TREATY

Now it was time for an unequal treaty to be promulgated. Just as the British had used military strength to seize Hong Kong from the Chinese in 1841, so Younghusband could use the same method to take another piece of land for Britain.

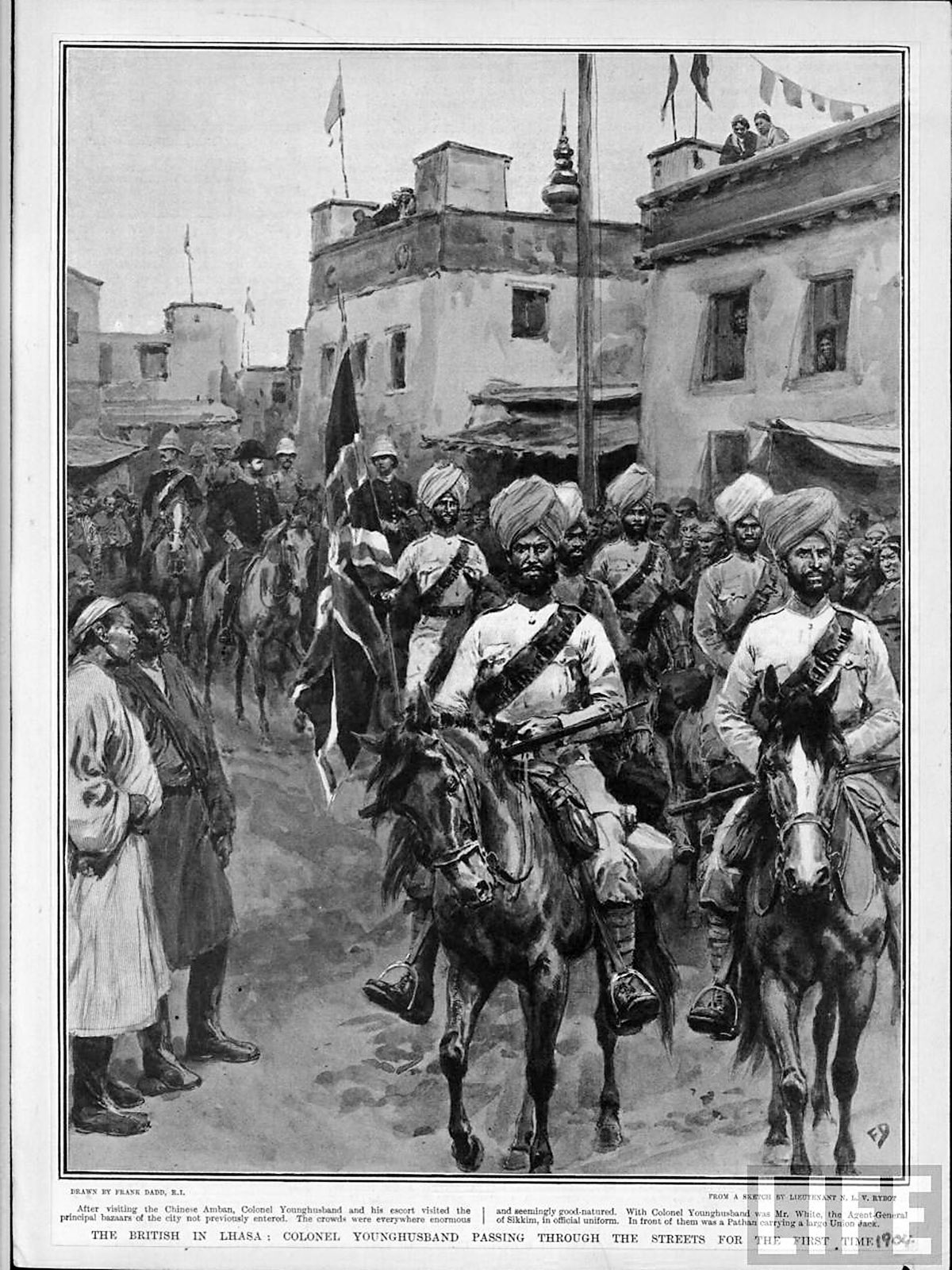

On August 30 1904, the British army marched into Lhasa, the capital of Tibet. They demanded that the authorities sign a document called The Convention of Lhasa (拉薩條約). This forced the Tibetans to pay a huge sum of money to the British. A large piece of land called the Chumbi Valley would be ceded to British rule until the money was paid.

The British General deliberately named a sum so large that he calculated it would take at least 75 years for the Tibetans to pay off the debt. So Chumbi would become a second Hong Kong in effect: long-leased British territory in Chinese land.

The British also insisted that Tibet would no longer be allowed to have relations with any other foreign powers. That would force the hidden Russia army to leave.

The authorities in Tibet signed. There was no choice.

FALSE PRETENCES

But as time passed, an embarrassing problem gradually came to light. There were no Russians. The rumours about a secret Russian army in Chinese territory were entirely false. An entirely non-existent threat had been used to justify an invasion.

To the credit of the British, while General Younghusband tried to present his side as heroic, some voices in the UK objected to what clearly a slaughter of untrained people armed only with medieval tools.

The British eventually toned down the demands of the Lhasa Treaty, and the Chinese leadership paid the bills on behalf of the Tibetans’ regional authority.

SPIRITUAL EXPERIENCE

But the story ends with a strange twist.

Towards the end of his stay in Tibet, General Francis Younghusband, on a “dreamy autumn evening”, climbed to a peak near where the soldiers were camping and looked back to the Kyi Chu valley.

He felt an extraordinary spiritual force sweeping over him. “I was insensibly suffused with an almost intoxicating sense of elation and goodwill,” he wrote down later. “The exhilaration grew and grew till it thrilled through me with overpowering intensity. Never again could I think evil, or every be at enmity with any man.”

He felt deeply sorry for the slaughter of Tibetans he had presided over, and became a deeply spiritual man: not conventionally Christian, but with a range of beliefs that one would today call New Age. One of the groups he founded commissioned the famous hymn Jerusalem, about Jesus visiting England.

His former domestic helper, Gladys Aylward, moved from the UK to China, where she spent the rest of her life working as a social worker and missionary, with her speciality being to help the Chinese government end the foot-binding tradition. Her life story become a hit Hollywood movie called The Inn of the Sixth Happiness, released in 1958.

REMEMBERED IN CHINA

Today, the 1903 invasion of Tibet has been largely forgotten in the west. But the Chinese remember what happened. A melodramatic 1997 Mandarin-language movie called Red River Valley dramatized the tale, and won several awards in that country.

But it’s a shame the story of the Tibet invasion is not more widely known. In theory, we learn from our mistakes. If the world remembered what had happened in that part of the world, 120 years ago, humanity might even have avoided some of the problems we see in the conflict in Europe today.

Image at the top shows Tibetans in a 1900 photograph from the Wellcome Collection.