The Economist magazine recently pushed dramatic statistical claims about the USA’s apparently world-beating economic growth. These figures raised the eyebrows of a prominent Harvard professor who responded that the numbers worked just fine – but only if China was omitted! The publication responded to his impudence by going on an energetic attack with a cover story showing that China as an economic growth story was over, finished, done, yesterday’s news. Richard Cullen looks at an amusing battle of words – which is probably not over yet.

EVEN WITHOUT Chat-bot assistance, it is fun to look up quotations and their origins online and then discover, for example, this quote reportedly from Winston Churchill: “The only statistics you can trust are the ones you have falsified yourself.”

And an earlier British prime minister from the 19th century, Benjamin Disraeli, allegedly said there were “three kinds of lies: lies, damn lies and statistics”. This bon mot was widely shared by Mark Twain.

What set me searching on this topic is a recent remarkable exchange between The Economist magazine, in the UK, and Professor Graham Allison of Harvard University, in the US. Professor Allison (below) explicitly referred to The Economist in this exchange.

The latter responded in somewhat thundering fashion and, although their target is not headlined, it quite clear who is in the cross-hairs.

But how did this all come to pass?

HOW IT STARTED

It began with a cover story and Leader article in The Economist on April 13 this year entitled: “The lessons from America’s astonishing track record”. The “tally-ho” tone is set within the opening stanza:

If there is one thing that Americans of all political stripes can agree on, it is that the economy is broken. … The last time so many thought the economy was in such terrible shape, it was in the throes of the global financial crisis.

Yet the anxiety obscures a stunning success story — one of enduring but underappreciated outperformance. America remains the world’s richest, most productive and most innovative big economy. By an impressive number of measures, it is leaving its peers ever further in the dust.

Professor Allison (famous for reintroducing the world, in 2015, to the Sparta vs Athens struggles from Ancient Greece, as way of framing the US mega-project to contain the rise of China) read this leader and it got him thinking. And writing.

THEN CAME THE REPLY

About two weeks later, on April 28, Graham Allison published a politely withering article in The Barron’s Daily, in the US, entitled, “The Inconvenient Truth About U.S. Growth”, which reviewed the aforementioned Leader from The Economist.

Allison is too well-mannered to begin with a quotation from any member of the Disraeli-Twain-Churchill troika noted above – but he does cut to the chase.

He first notes how The Economist claimed that the US economy was “leaving its peers even further in the dust” and how this assertion, that the American economy is still world-beating, offered welcome reassurance within otherwise disheartened sectors in Washington. Even better, The Economist emphasized that, “America’s dominance of the rich world is startling.”

Allison then shreds this boosterism-balloon in mid-air with an exceptional, initial verbal missile:

The inconvenient truth, however, is that the Economist reaches this stunning conclusion by excluding the U.S.’s only true peer: China. Instead, it compares the U.S. with competitors in the G7: Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, and the U.K. In that race the U.S. is not only ahead but extending its lead. But to declare the U.S. the winner for outrunning other members of the G7 is like awarding an American Olympic sprinter the gold medal by excluding world champion Usain Bolt.

Ouch!

But there is more to come. Allison notes how:

Except for a few eccentric academics and editorialists who have been promoting a “peak China” theory, everyone is expecting China’s economy to grow faster than the U.S. this year. They are also expecting it to grow faster than the U.S. next year. And in 2025 and as far beyond that as any eye can see. The only question informed analysts and investors are debating is: How much faster than the U.S. will China’s economy grow this year? Twice as fast? Three times the U.S.? More?

He also explains how he has placed bets with colleagues that the US economy will not grow faster than China’s – or even half as fast.

And he suggests that serious Peak China believers seek out folk willing to take bets on the reverse view, favouring US economic out-performance of China. He does not specifically offer to take those bets – but there may be laws in the US frowning on doing that in a newspaper article. (It is a well-known fact that they have a surfeit of lawyers in America – and, thus, a bewildering cornucopia of laws.)

Dear me! The Economist found itself firmly brought back to Earth – or Exoceted as we used to say some years ago.

However, this shocking Harvard-impertinence could not be left unanswered.

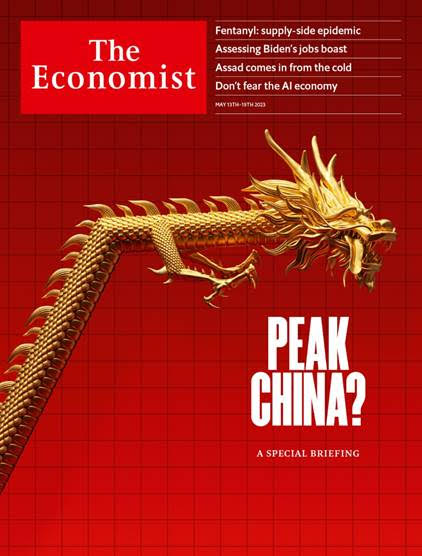

By May 13, a conspicuous counter-offensive was mounted. On that day, The Economist produced a Special Briefing issue on Peak China complete with a slack-necked, gasping golden dragon graphic on a blood-red cover:

Inside, a minor squadron of related narratives, including a fresh Leader, advanced many reasons to show why Peak China (whatever that specifically means) was very likely a matter of when not if – asking, for example: ”How soon and at what height will China’s economy peak?” These articles, written in the wake of Allison’s searing critique, leave a lingering impression of articulate but rather over-cooked, thin-skinned petulance.

The Economist recently created a virtual War Room to bring us its new War Room Newsletter presumably to keep its readers at action-stations with respect to the Ukraine War. (A dreadful idea, as it happens – the war-mongering overtones are unmistakable.) After this exchange-based episode we could be forgiven for wondering if The Economist also, now, has a Peak China Room.

Allison concludes his Barron’s article with an acute test: The US economy, he wrote, stood, in real annual GDP terms, at around US$20 trillion at the beginning of 2023, and China’s at around US$16 trillion – a difference of US$4 trillion.

Thus: If America were leaving its true, closest peer in the dust at the end of 2023, that gap will have widened.

Once again, place your bets ladies and gentlemen.

And watch this space.

Richard Cullen is a law professor at the University of Hong Kong and a popular writer on current affairs.

Image at the top by Fridayeveryday.