As U.S. politicians call for laws against Chinese people buying property in the country, there are fears that the dark mentality behind the infamous Chinese Exclusion Act is still present, and may even be growing. Portia Chung reports.

ISSUES INVOLVING PEOPLE with Asian roots are burning hot in the headlines in the United States right now. Arguments over race-based university access, fears about the rising number of anti-Asian hate crimes, concerns over the local repercussions of geopolitical tensions—these and other issues are being discussed among members of what is supposed to be a quiet “model minority”.

However, these concerns are not new to Asian communities. There is a deep-seated anti-Asian intolerance in the country, says historian Mae Ngai. “If we don’t understand the history of Asian exclusion, we cannot understand the racist hatred of the present,” she wrote recently in The Atlantic.

The present writer read Mae Ngai’s “Racism has Always Been Part of the Asian American Experience” and you may wish to do the same. Here’s the link.

Her insight inspired me to write this article, in which I shed more light on the consequences of harmful ideas and tropes that emerged from the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.

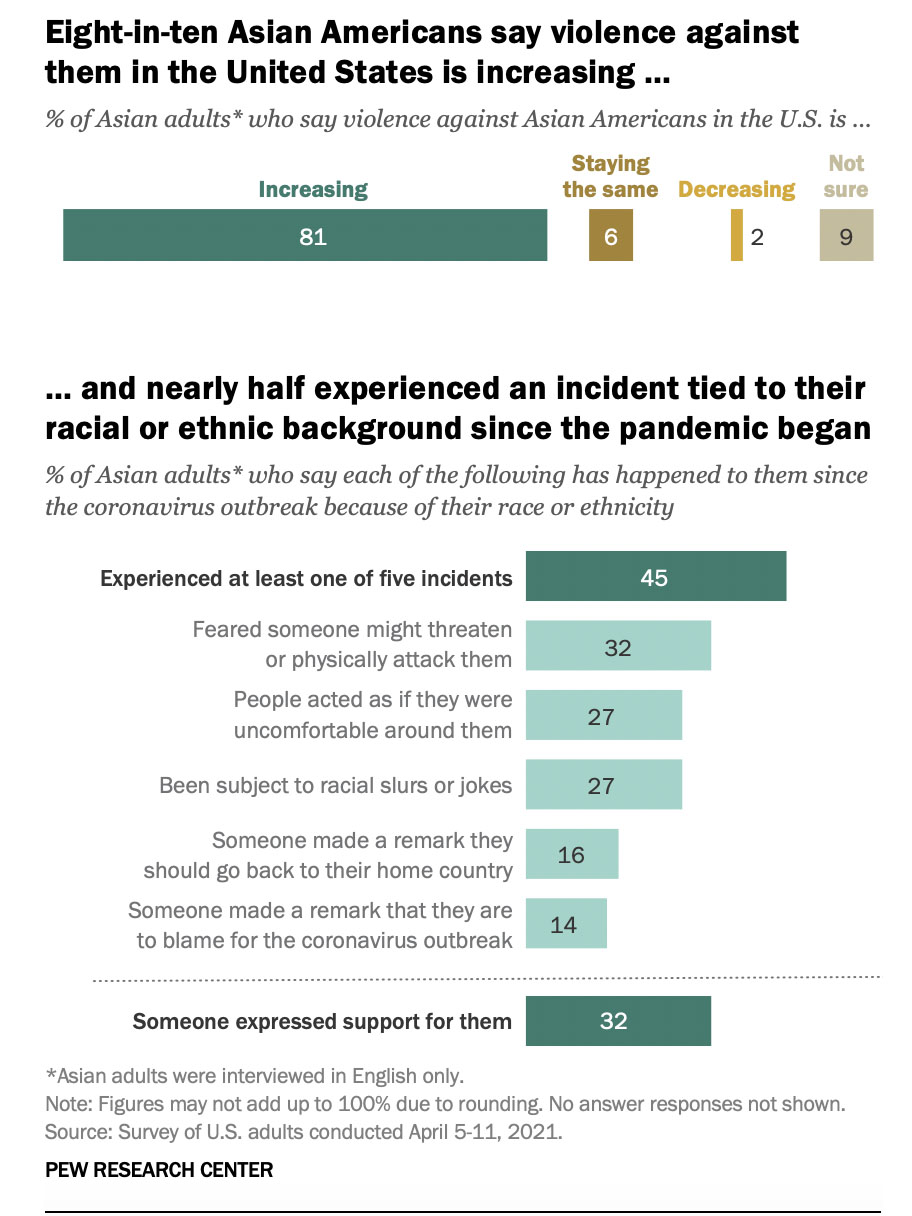

It is no secret that anti-Chinese and anti-Asian sentiment skyrocketed following the Covid-19 pandemic. Now, even three years since the virus took its hold, anti-Asian hate is still simmering.

HISTORY OF CHINESE EXCLUSION

So, allow me to give a brief history of Asian exclusion.

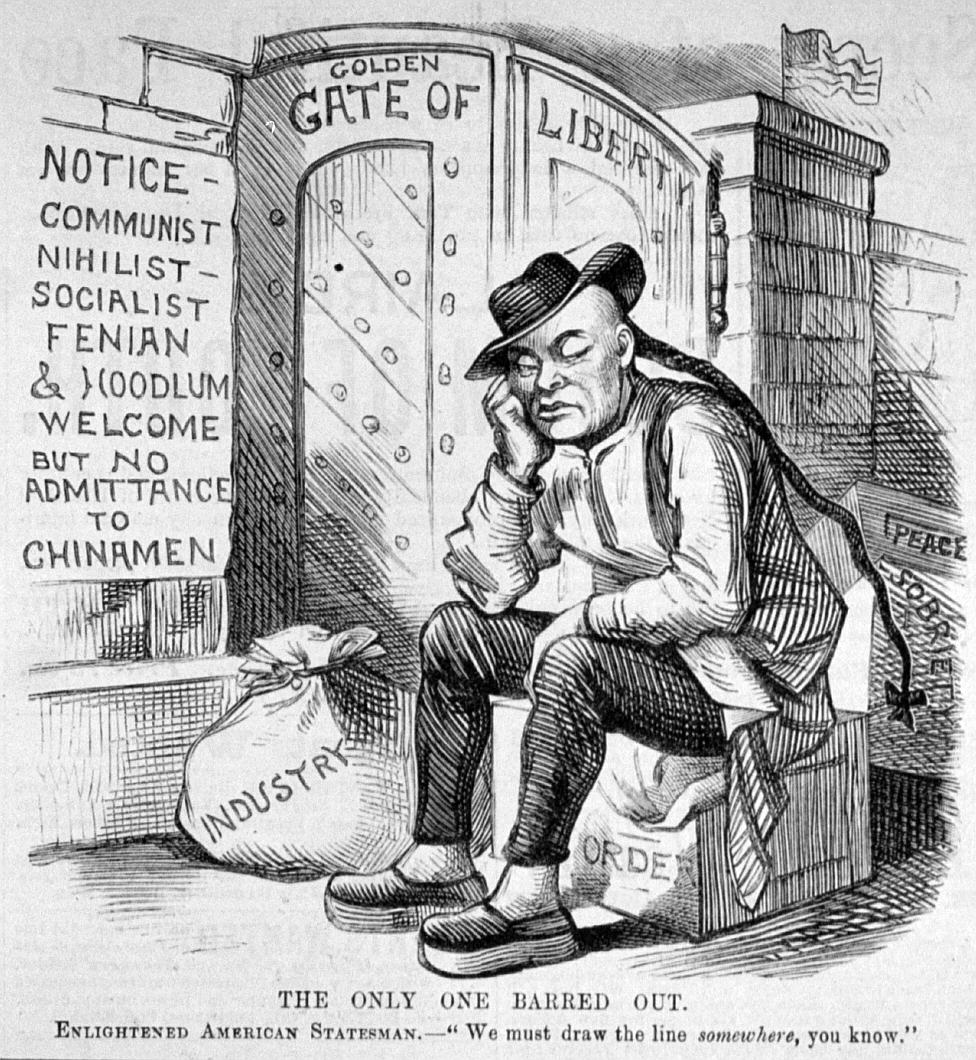

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was passed to prevent the influx of Chinese immigrants to the United States.

In the late nineteenth century, the U.S. government imported Chinese workers to build transcontinental railroads, causing strife among the white working class who felt their jobs were threatened by cheap Asian labor.

Used as a scapegoat for white economic ills and declining wages, Chinese workers were heavily discriminated against by the American public at large.

Courtesy of the California History Room, California State Library, Sacramento, California

Immigrants were lynched by hateful mobs, and survivors watched as their Chinatowns were burned to the ground.

This pervasive anti-Chinese sentiment coupled with concerns about maintaining white racial purity, pressured the United States government to pass legislation surrounding the issue—not to protect the battered Chinese community, but to greatly limit the rights of the aliens from across the Pacific.

Thus, the first racially discriminatory law in American history was born.

THE CHINESE EXCLUSION ACT OF 1882

On May 6, 1882, President Chester A. Arthur signed the Chinese Exclusion Act into law. The act suspended Chinese immigration to the U.S. for ten years, and made Chinese immigrants who had already entered the country ineligible for naturalization.

Ten years later, in 1892, the Geary Act, which reinforced and extended Chinese exclusion from the U.S. for another ten years, was passed.

The Geary Act also stipulated that Chinese citizens had to carry special documentation with them at all times. If caught by authorities without the necessary paperwork, they faced punishments of imprisonment, hard labor, or deportation back to China.

Bail was only an option if the Chinese detainee could be vouched for by a credible witness—who had to be a white person.

INTERTWINED HISTORY

By presenting the historical dynamics that produced anti-Asian racism in the United States, Ngai helps the reader understand how deeply ingrained anti-Asian hatred is in our society.

Her argument extends to other groups, such as African Americans, whom she believes have an intertwined history of racism with Asian Americans.

Ngai draws a connection between the two groups by asserting that Jim Crow laws and the Chinese Exclusion Act were both “related projects of white supremacy” in that the catalyst for the legislation was racial hatred and a belief that neither group belonged in America.

Indeed, African Americans were marginalized in every aspect of American society. Jim Crow laws legalized racial segregation and targeted black participation in society by denying voting rights, equal access to education, and job opportunities from black Americans.

It should be noted that African Americans and Asian Americans have had distinct experiences as minority groups in the U.S., and those experiences should not be compared to one another. However, the origins of these two long histories of discrimination are undoubtedly based on the racist ideals America was founded upon.

Racist theories against Chinese immigrants… have haunted Chinese Americans ever since.”

John Bigler

Ngai claims that these prejudices still exist in politics and culture today. Such a claim is central to the core argument that she opens the article with.

Ngai quotes California Governor John Bigler, whose claim that the Chinese were being sent to the U.S. under illegal contracts to undermine the American labor force, inspired associations of “colonialism and slavery” which incited “…racist theories against Chinese immigrants, and have haunted Chinese Americans ever since.”

MODEL MINORITY MYTH

One of the theories that emerged from this era is contemporarily referred to as the “model minority myth”.

In order to appeal to the white American public and advocate for social inclusion in the early twentieth century, many Asian Americans labeled themselves as “quiet, good workers, good students, and respectful of their parents”, qualities that define the “model minority myth” that plagues so many Asian communities today.

Coined by University of California sociologist William Petersen in 1966, the term refers to the perception of Asian Americans as having achieved high levels of success and prosperity in American society.

Today, the myth inspires popular assumptions that Asian Americans are hardworking overachievers engaged in math and science and always at the top of their class.

HARMFUL REPERCUSSIONS

Perhaps this characterization of Asian people seems benign, even complimentary. However, the model minority idea has had harmful repercussions for Asian communities.

One such repercussion is decades of Asian people trying to fit the box of a model minority to prove their belonging to white Americans around them. Decades of feeling like perpetual outsiders has lent itself to behavior that seeks neither to disrupt nor go against the grain in an attempt to ingratiate Asian Americans with white Americans.

Oh, and not to mention the inordinate pressure and expectation placed upon Asian American children to live up to high academic and professional standards.

Being perceived as peaceful, smart, and financially well-to-do, many believe that Asian Americans have had no reason historically to complain about their condition in the United States. Most assume that they do not require uplifting since racism could not possibly affect such a non-threatening group.

This has decidedly removed Asian Americans from conversations surrounding racial justice in the U.S., regardless of the systemic prejudices that are constantly overlooked.

NOT HOMOGENOUS

This disregard can be attributed to the fact that Asian Americans are often viewed as a homogenous group. In reality, the term “Asian American” can refer to a multitude of ethnic backgrounds, all of which come with distinct experiences. Measuring Asian Americans as a group both fails to recognize their individuality, and also ignores those who do not fit the stereotype.

In fact, many Asian Americans do not fall into this “well-to-do” category: Asian Americans are the ethnic group on the lowest rung of the poverty ladder in the U.S. The Pew Research Center found that in 2019: 12 out of 19 Asian origin groups have poverty rates as high or higher than the national American average.

Additionally, the idea that Asian Americans are diligent, disciplined, and subservient workers has contributed to high employment rates, yes, but low rates of Asian Americans in leadership positions.

This extends beyond the workplace and into American politics and the American cultural sphere– Hollywood, the music industry, etc.– where there is a general absence of Asian representation. Therefore, Asian Americans lack substantial political or cultural sway, influences that are integral to the progress of the Asian American experience.

These are legitimate concerns that deserve to be addressed.

So, no, racism does not elude Asian Americans. This was evident in 1942 when 120,000 Japanese Americans were kept in internment camps.

This is evident today when race-baiting politicians dub a global pandemic the “Kung flu” and the “Chinese virus”, leading to widespread racial hatred and violence.

The model minority myth is just that, a myth. It is essential that society as whole recognizes its effects and stops basing its set of beliefs on a harmful misconception.

FETISHIZATION OF WOMEN

Aside from the model minority myth, anti-Chinese immigration sentiment also contributed to the fetishization and exoticization of Asian American women.

In her article, Ngai describes an act that predated Chinese exclusion: The Page Act of 1875 that barred Asian prostitutes from entering the country.

The process of interrogating any woman upon entry to ensure that she was not a prostitute, disincentivized Asian women from emigrating to the US at all, and contributed to the established stereotype that “Oriental” women were dangerous.

These connotations of prostitution and sexual deviancy had large consequences both in America and overseas. Ngai states that, “The prostitution of Asian women for American servicemen is an enduring feature of the U.S. military experience in Asia.”

AN EAST ASIAN ISSUE

And U.S. militarism has a significant presence in East Asia.

In 2020, the U.S. declared that it would maintain the station of 100,000 troops in the region.

This may not come as a welcome announcement to all local residents, especially the women. Throughout the twentieth century, U.S. military personnel carried out acts of sexual exploitation and physical abuse of East Asian women.

During the Philippine-American War, World War II, and the Vietnam War, American servicemen were known to solicit sex workers, leading often to prolific sexual abuse and sex trafficking rings.

In fact, according to research conducted by the feminist peace organization Okinawa Women Act Against Military Violence, U.S. troops in Okinawa have committed over 4,700 reported crimes since their stationing in 1972. Unfortunately, the real number is likely much higher, as much of the violence against women remains unreported. Aside from the shame and fear endured by the victims, the frequency with which sexual crimes are committed has led to a general lack of faith in the perpetrators being convicted.

As a result, victims’ health has not been properly addressed. HIV, AIDS, and sexually transmitted diseases are common throughout populations of women who work near military bases. Many face battles with mental illness or are forced to undergo unsafe abortions.

On the home front, films and artwork produced after US-led wars in East Asia were the stimulus for the trope that East Asian women were exotic, hypersexual, and submissive.

This stereotype has become ingrained in the fabric of American culture.

Just two years ago, in March of 2021, Robert Aaron Long carried out the murders of six Asian American women motivated by a sex addiction that contradicted his religious beliefs.

Long targeted Asian-run spas in Atlanta, Georgia to “eliminate temptation” posed by his perception of the hypersexuality of Asian women. Long’s unspeakable act of violence demonstrates the danger of fetishizing Asian women. It is crucial that this harmful narrative be ended.

YELLOW PERIL

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 entrenched “Yellow Peril” in the hearts and minds of the American people.

The repercussions have been severe: decades of racial prejudice that has ravaged the Asian American community.

The act is a prime example of the enormous influence that government legislation has on shaping public opinion and how laws can be weaponized to incite hate.

The year 2016 began an era that would entirely change the landscape of immigration policy in the U.S. The “Muslim Ban”, family separations, expedited removals, and laws surrounding legal immigration were deeply rooted in racial discrimination and have been detrimental to both Muslim families and to anti-Muslim sentiment in the U.S.

Even after the laws have been repealed, their effects do not simply disappear– they will continue to have lasting effects on the Muslim community. The Chinese Exclusion Act proves this to be true.

American voters must directly confront our deeply held biases about marginalized communities and be intentional when electing government officials and legislators.

Image at the top is a montage by fridayeveryday.