It started with a death in the river, the legend says. But no one could predict the scale of the repercussions – which are marked today, more than 22 centuries later, with international sports events. The original festival has deep mainland Chinese roots, but was popularized worldwide by the people of Hong Kong. The two communities share deep cultural roots.

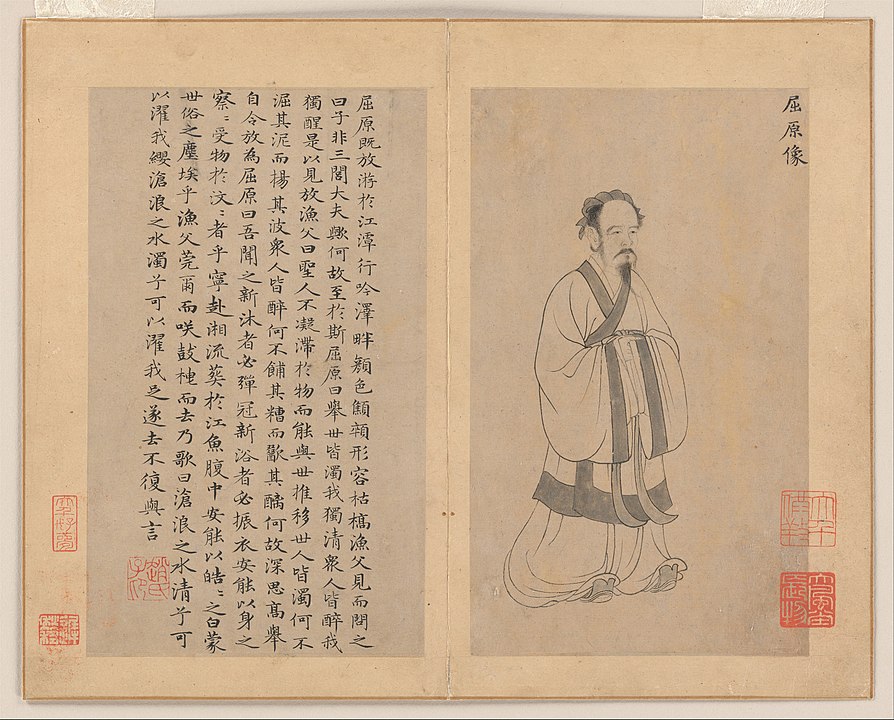

THE POET QU YUAN picked up a rock and waded into a river to drown. Why did he want to end his life? Some scholars say the “people’s poet” decided to martyr himself after his state was conquered by outsiders. Others said he wanted to maintain the innocence he had shown during his lifetime in the face of corrupt enemies acquiring power, inside and outside the government.

Clutching the heavy rock, he kept on walking, eventually disappearing under the surface of the Miluo River, a tributary of Dongting Lake in China’s Hunan Province.

But he was loved—and people who saw him walking into the water quickly spread the word. “The poet’s drowning – someone save him!”

RESCUE MISSION

People dashed for the boats. They pulled out their teak-carved canoe-shaped vessels and paddled from the bank as fast as they could go. But they could not find him—presumably he held tight to the rock to keep himself under the surface.

Then watchers noticed a stirring in the water, believed to be caused by sea creatures. Were fish or sea monsters heading to consume the poet’s body?

People started beating drums to scare away the fish. Others threw items of food into the water to distract them.

But time passed, and Qu Yuan could not be found. When it became clear that he would not be saved, they threw food, wrapped in triangular packages, into the water as a sacrifice to his departing spirit.

But there were two endings to the story: one typically mystical, and other very practical for an agricultural society.

First, the legend grew that his spirit was immortalized and added to a group known as the Lords of the Water—a five-strong group of water deities headed by Yu the Great, the first emperor of China, known for his work fighting against the great flood.

Second, Qu Yuan’s death, which took place more than 22 centuries ago, became associated with an important date on the people’s calendar.

THE DRAGON KING’S PROMISE

The farming people of ancient China had long noticed that the sun was always highest on the fifth day of the fifth month on their lunisolar calendar. This was the longest day of the year, so they called it Duan Wu, with the first word indicate the zenith (highest point) and wu meaning “five”.

But they were agriculturalists, and knew that heat and sunshine would perform wonders for their crops ONLY if they also got the right amount of rain.

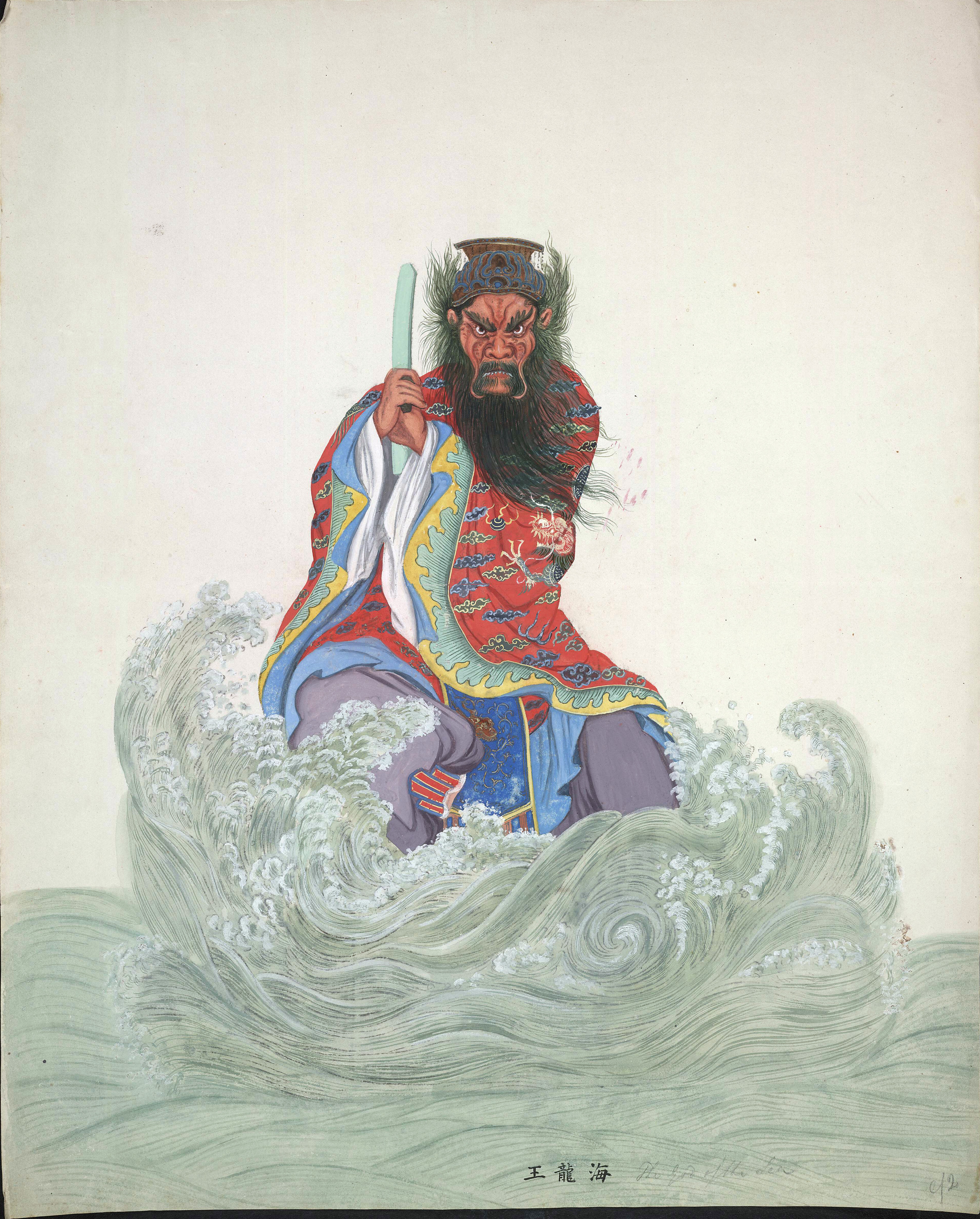

So they needed to make a deal with the Dragon King, who was believed to control all waters on the planet – that meant the waters of the earth (the seas, lakes and rivers), and the waters of the heavens (the rain, the mist and the clouds). Westerners may link to think of him as the equivalent of western mythology’s Triton, the Sea King, but with added control over the sky, the weather, and the elements.

Keep him happy, the belief said, and he would promise a good harvest. The dragon worship ceremonies of this important festival are believed to have started to incorporate dragon boats between 22 and 25 centuries ago in southern central China—water vessels were the natural way to connect humanity with the water.

The agricultural rituals of Duan Wu and the poet’s death became associated – along with themes of boats, drums, special foods, and dragons.

THE FESTIVAL SPREADS

The celebration of the event spread to numerous communities in the region, including Singapore, Malaysia, Cambodia, Korea, Vietnam and Japan.

But while celebration of Duan Wu and dragon boat events have taken place ever since, another important development took place very recently.

It was recast as an international sport in 1976 in Hong Kong. Standardized rules were drawn up. There are 18 to 20 people in a standard boat, plus someone to steer and someone to beat the drum.

Hong Kong people are often portrayed in the western media as separate and hostile to mainland Chinese, but that’s the tiny minority journalists prefer to interview. In truth, both communities share a deep interest in Chinese traditions.

The boat races were popular. Engineers got involved and redesigned the boats to be made of lightweight carbon fiber—in the past, they had been made of heavy teak wood.

When Queen Elizabeth of England visited Hong Kong in the 1970s, she was treated to a dramatic display of dragon boat racing, which she watched from the balcony of a floating restaurant.

The Chinese government added the Dragon Boat Festival to the list of national holidays in 2008—and an ancient tradition was now fully revived.

Today, dragon boat racing is recognized as a serious sport, organized by an International Dragon Boat Festival organization. In Hong Kong, participants train for many months of the year. It has been recognized by the Olympic Movement as an important sport, and the International Olympic Committee maintains it as a potential new sport to be added to the list of events at the Olympic Games.

The poet Qu Yuan, if he is watching from his seat among the Lords of the Water, must be delighted.

Image at the top shows a dragon boat in Singapore, by V Menkov /Wikimedia Commons.