THE ORIGINAL SILK ROAD quietly crept into existence over many years, but ended up transforming much of the world.

China’s new Silk Road is already doing the same.

A total of 151 countries were represented at the Belt and Road Initiative gathering last week—and 215 new BRI projects were announced for the coming months.

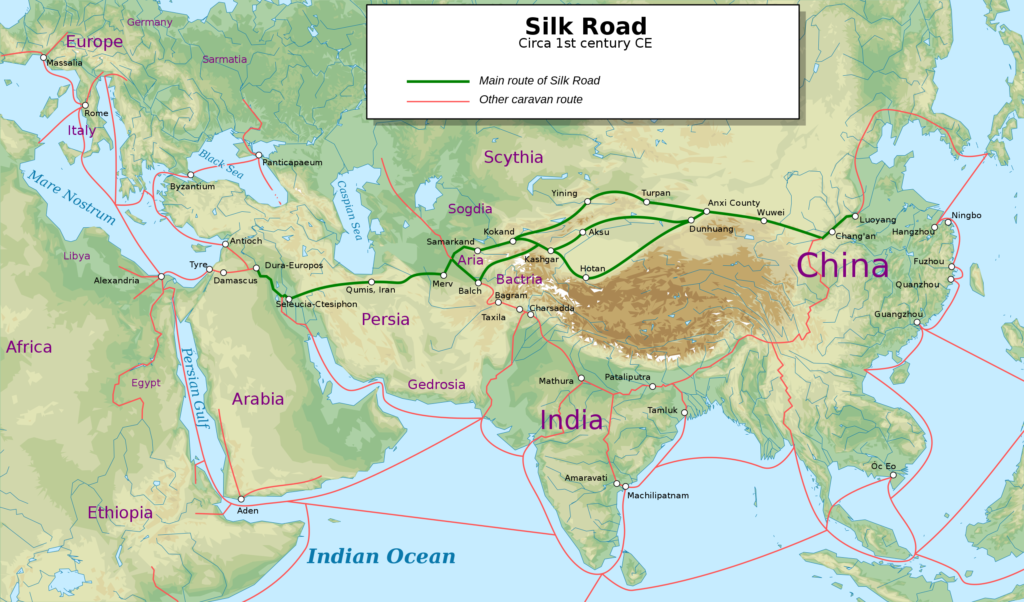

But how exactly could the Belt and Road Initiative, or BRI, change the modern world? To answer that question, let’s start by looking back at the original Silk Road.

Although the Silk Road could be said to be simply a byproduct of free trade, through it, a whirlwind of events were set into motion, causing ideas and cultures from opposite ends of the world to collide. It ended up affecting the world in many unexpected and peculiar ways, shaping humanity as we know it today.

SILK CLOTHES AND THE FALL OF ROME

Around 30 BC after conquering Greece, Gaul and Egypt, Rome’s mighty gaze turned East. Roman Statesman Cicero wrote that Asia was indescribably wealthy, its harvests the stuff of legend, the variety of produce incredible, and the size of its herds and flocks simply amazing. All kinds of exotic goods were coveted – especially Chinese silk.

As trade between Rome, Persia, Bactria and China increased, so did the popularity of silk in the Mediterranean. Roman writer Pliny the Elder complained about inflated prices, saying that it was a scandal, a hundred times the real cost.

Huge amounts of money were being spent annually, for “us and our women” from Asia, with as much as 100 million sesterces per year being pumped out of the Roman economy. This astonishing sum represented nearly half the annual mint output of the empire, and more than 10% of its annual budget.

From the Chinese perspective, the Roman Empire (which they knew as the Great Qin), was renowned for its abundance of gold, silver and precious jewels. Even though China and Rome rarely had direct dealings, it maintained a strong trade relationship with the Kushan and Parthian Empires (modern day Afghanistan to Iraq).

One Chinese source notes that at least ten trips were made to Persia in a year, buying foreign commodities such as Red Sea pearls, jade, lapis lazuli and as well as consumables such as onions, cucumbers, coriander, pomegranates, pistachios, and apricots. In particular, the peaches from Samarkand (modern Uzbekistan) were highly prized for their large size and vibrant golden hue, earning them the name “Golden Peaches”.

The capital outflow of this scale had far reaching consequences, especially the growth of local economies along the trade routes. Villages turned into towns and towns turned into cities, as business flourished and communication and commercial networks mushroomed. Cities such as Palmyra prospered from the trade linking east to west, as seen in the increasingly impressive architectural monuments built during that time. Palmyra has been called the ‘Venice of the sands’. Likewise, the ancient city of Petra, became one of the wonders of antiquity thanks to its position on the route between the cities of Arabia and the Mediterranean.

NEGATIVE EFFECTS

Another unintended effect, as the Persian economy boomed, was that Rome found itself in an increasingly unfavourable position. Its opulent lifestyle had taken its toll: the empire, reliant on expansionism, was unable to sustain the same growth. Troubled by the economic prospect of dwindling tax revenues and increasing costs to defend Rome’s borders, Emperor Diocletian ordered an empire-wide count of all its assets, and an edict that standardised prices for all goods.

The extent of this program was such that a recent archaeological discovery in Turkey found that everything from horseradish to “purple low-rise Babylonian style” shoes had a price limit set by Rome’s tax inspectors. The life of the old, disciplined, warlike Rome faded away. In its place, a lifestyle of hedonism and avarice took its place.

As to whether the trade of exotic Eastern commodities was the cause or a result of theiR materialistic lifestyle is up for dispute, but there’s no denying that the Silk Road had a much greater impact than may have been originally expected.

EXCHANGE OF IDEAS

Although the BRI isn’t perfect, as it has landed itself in some debt trouble since the pandemic, the facts and figures tell us that the outlook is still positive. Sir Douglas Flint, former HSBC Chairman recently said that the BRI has so far been “one of the biggest, if not the biggest, facilitator” of the achievement of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, and has an “incredibly positive” impact on regional and world development.

Image at the top from fridayeveryday.

Joshua Cheung is a student at Eton College, London.