The biggest international trading venture in world history is 10 years old.

But there’s an extraordinary tale behind the Belt and Road Initiative, or BRI.

And that’s the story of the exceptional Chinese Diaspora experience, which laid the foundations for the infrastructure project’s success.

This Chinese macro-migration endeavor, individual by individual, long predates the remarkable BRI, which is, today, measurably retracing the diaspora’s pioneering footsteps. Richard Cullen reports.

THIS YEAR, CHINA and the world are witnessing the 10th anniversary of the inauguration of the Belt and Road Initiative. The BRI is not a perfect success story, of course: nothing on this extraordinary scale could be. But the complications, obstacles and deficiencies have been worked-on as they have materialized.

Moreover, its overall positive, public infrastructure achievements, not least in Africa, have been extraordinary – and all secured within the span of a decade.

According to the German online data-gathering platform, Statista:

- 149 countries have joined the BRI (the United Nations has 193 Member States, incidentally).

- The investment in BRI projects across these countries since 2013 now totals around US$1 trillion.

- China’s trade with major BRI countries had grown to almost 30% of all Chinese trade in 2020, doubling in the period since 2015.

Globally, thousands of miles of new roads, plus new railways, bridges, hospitals and schools, for example, have been built under the BRI, especially across the Global South.

Sir Douglas Flint, former HSBC Chairman (pictured) recently said that that BRI was “one of the biggest, if not the biggest, facilitator” of the achievement of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, and has an “incredibly positive” impact on regional and world development. It is said that the BRI has created over 400,000 jobs and has lifted “nearly 40 million people out of poverty”.

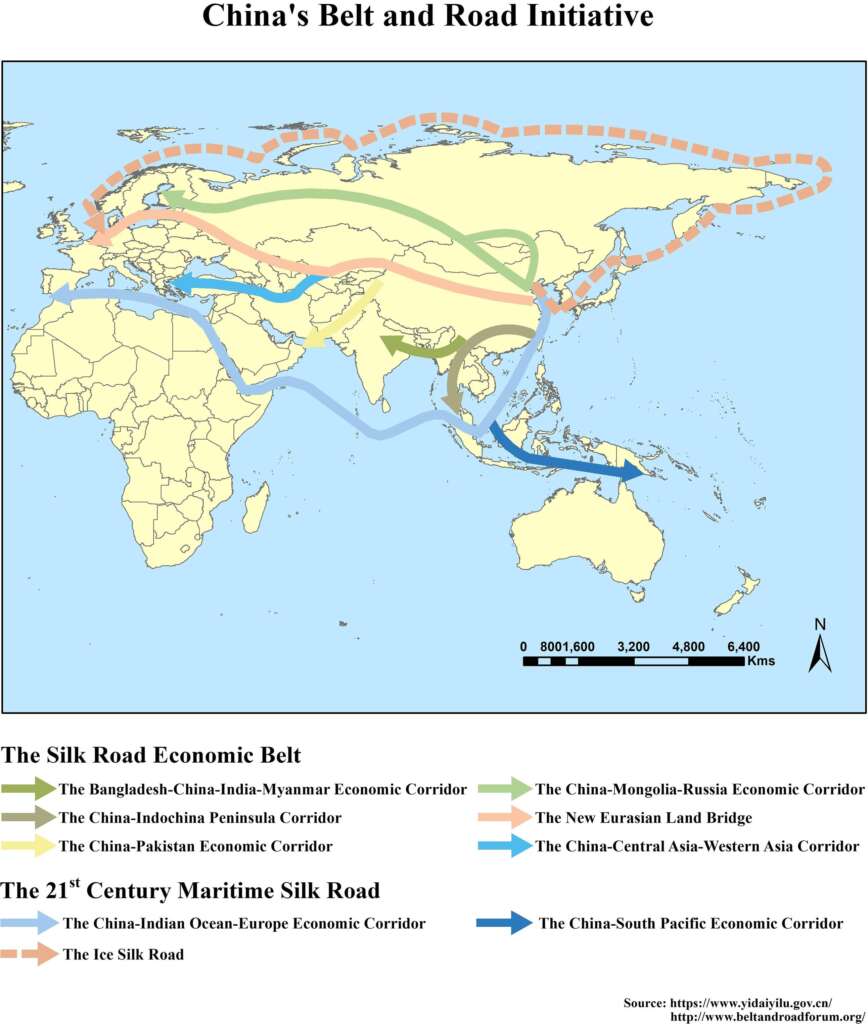

Unsurprisingly, there has been significant rediscovery and discussion, over the last 10 years, of the original, formalized version of the “Silk Road” (across Eurasia) and the “Maritime Silk Road” (reaching out via the South China Sea).

Various scholars have observed how the establishment of each of these dates back over 2,000 years to the expanding trade fostered during China’s Han Dynasty (206 B.C.–220 A.D.). Eventually these once flourishing trade routes faded away, not least in the wake of the rapid European global expansion (and Euro-imperial colonialism) ushered in by the Age of Discovery, which had begun by the 15th century.

THE MODERN CHINESE DIASPORA

What I wish to review here are the less-formal but still exceptional, extended global foundations, powered by individual Sino-migratory enterprise, which historically underpin the entire BRI project.

During the height of the importance of the two early Silk Roads just noted, this did not trigger any significant migration of Chinese from China. Trading powers largely stayed within their own geographic locations – and traded.

In fact, as several scholars, including Professor Wang Gungwu and Lynn Pan have explained, it was after the Euro-colonial age gained such traction that Chinese people began migrating in large numbers.

Chinese junk in Borneo.

Many, often facing terrible scarcity and desperately determined, began to perceive: offshore trading prospects; an opportunity to seek a better life; or an opening to provide hard-working, low-cost indentured labour, for example. Indeed, without this Chinese labour it is almost certain that the transcontinental railways in the US and Canada could not have been built so swiftly and effectively (at great human cost).

Chinese women and children in Brunei, c. 1945. (c) Lt A.W. Horner.

Colonizing, European governing and business elites mainly looked favourably on these migration patterns. As Denis Mc Cormack noted in a review of Lynn Pan’s remarkable book, Sons of the Yellow Emperor, new Chinese arrivals were valued for their industriousness, their ability to cope with low-paid hard work and their business acumen – and business connections.

Subsequently, as Lynn Pan explains, local (including European) residents in the destination colonies, became resentful about the competition Chinese immigrants introduced into their societies (by and for the benefit of certain elites). Anti-Chinese immigrations laws in due course followed in the US, Australia, Canada and beyond.

Chinese gold miners (group on the right) working alongside white miners at Auburn Ravine in central California, 1852. Courtesy of the California History Room, California State Library, Sacramento, California

According to a UNESCO report from 2021, the total number of Chinese living offshore today (including descendants) is over 60 million – more than the current population of Italy.

TAKE YOUR CIVILIZATION WITH YOU

Several facets of the impact of this very large Chinese diaspora are notable, including: how globally wide-spread it is; and, despite recurrently unpromising and regularly hostile circumstances, how so many Chinese immigrants have, time and again, built fresh success into their lives – and that of their families – in far-off places.

Simon Leys, the renowned Belgian-Australian Sinologist, once observed how the essence of Chinese civilization could best be found in the deeply shared, Confucian-based collective understanding of what being Chinese meant. He contrasted this collective worldview with the European collective view of itself, which relied far more on its embodiment in majestic material constructions (cathedrals and like imposing buildings).

A Chinese friend succinctly summed this up some years ago after his first extended visit to the UK. China, he noted, had a recorded, developed history that was far older than that found in Great Britain. Yet, if you simply considered the buildings in the UK, it looked to be the measurably older civilization.

The Chinese are happy to create buildings, while the British celebrate their oldest ones. Image of Shanghai by Pexels.

It follows from Ley’s understanding, that one reason Chinese have migrated so successfully to so many different countries, is that they can more readily take China with them where ever they go, while commonly maintaining continuing, inter-generational links to the ultimate land of origin. Notwithstanding the turbulent history of China over the last 200 years, it has remained a civilization that is remarkably well grounded. And that grounding endures, as Lynn Pan explains, for so many of the sons (and daughters) of the Yellow Emperor who have migrated far and wide over the last several hundred years.

This 1841 painting shows “Sangleys”, a term for Chinese in the Spanish Philippines.

GO SOUTH YOUNG MAN

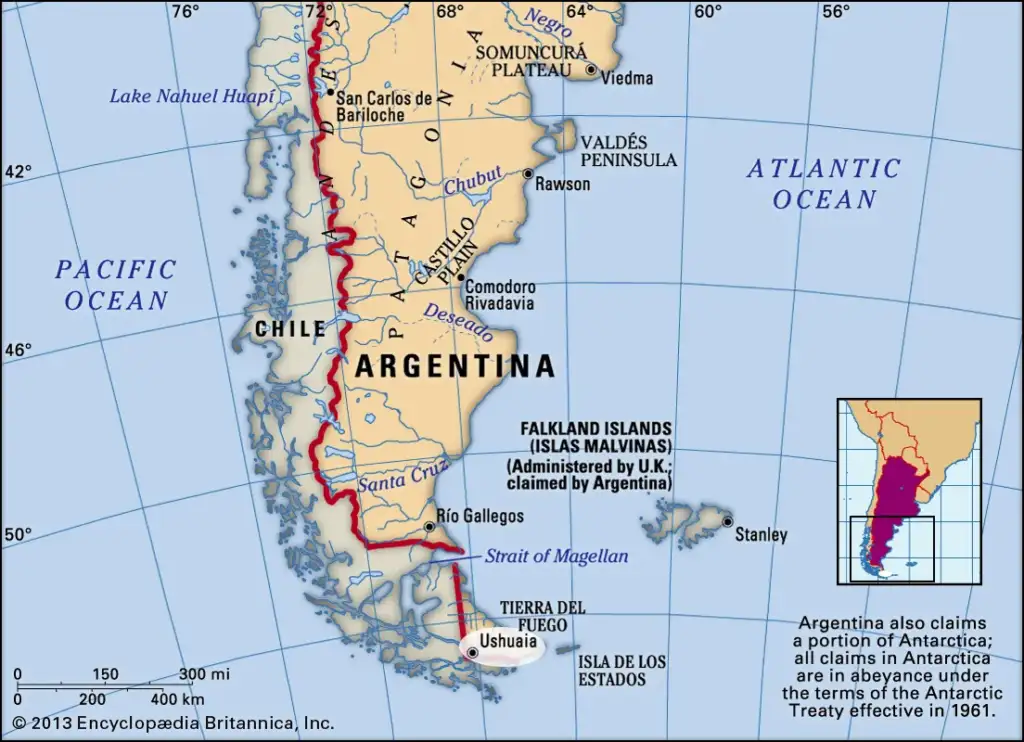

Tierra del Fuego (“Land of Fire”) is the name of the archipelago at the very southern tip of South America. It was given this name by Ferdinand Magellan during the extraordinary first European circumnavigation of the Globe, from 1519 – 1522.

It is a place of fierce weather that is divided between Argentina and Chile. Its southern tip lies at 56 degrees south, which is very far south, indeed – around ten degrees closer to the South Pole than New Zealand’s most southerly point on Stewart Island. Tierra del Fuego, despite its remarkable and inhospitable location, is still comparatively well settled. The main city Ushuaia (in Argentina) has a population of over 80,000.

Some years ago, when I was completing some general reading, I was surprised to discover that Ushuaia has had a Chinese restaurant for many decades. I just rechecked this Chinese restaurant situation and, today, three are listed, online. Click here to see them.

The US-based hamburger chain, McDonald’s, is rightly renowned for its remarkable global spread. As of today, I could find no McDonald’s in Tierra del Fuego – and the nearest one looked to be a long way further north in Argentina.

BOX HILL – THEN AND NOW

I recall thinking, when I first discovered this most southerly Chinese restaurant in the world, how it was indicative of the exceptional enterprise of numerous members of that large Chinese diaspora.

And I was recently reminded about this adventurous spirit during a visit to Melbourne.

Australia has weathered the economic turmoil of the last several years comparatively well thanks to its fractious but still robust trading relationship with China. Nevertheless, the economy remains notably subdued compared to five years ago. In one suburban shopping street after another, many premises remain vacant, while the one business-sector growing robustly has been charity shops. These second-hand outlets, now often very large, are mainly run by the goodwill arms of the Salvation Army and other churches, where much labour is voluntary and the stock is donated.

But I did rediscover one suburban area where a distinctive commercial vibrancy was evident.

Over 50 years ago, one of my first jobs in Melbourne was writing for a low-ranked motor magazine. It was run on a shoestring. Our office was a cramped portable shed erected, by arrangement, in the back yard of a printing works in the eastern suburb of Box Hill. The main building housed a primary printing press for the Salvation Army in Melbourne and it was here that “Australian Auto-Sportsman” was printed alongside “The War Cry”.

Box Hill and surrounding eastern suburbs were well populated with industrious members of certain Christian churches, including the Salvation Army, Baptists and Seven Day Adventists. One distinctive feature was that, through the exercise of local council powers (and in keeping with the temperance beliefs of these churches), many of these suburbs were “dry” – no licensed premises were allowed.

Box Hill was named, by 1861, after a town and nearby hill in Surrey in the UK (a pivotal passage in Jane Austen’s novel, Emma, published in 1815, is set at the original Box Hill). Melbourne’s Box Hill lies about 14 kilometres east of the Central Business District (CBD), which hampered its early development. Though, as more public transport connections were established, it began to grow significantly.

Since the turn of this century, the population of Box Hill has almost doubled, with most of that increase coming from mainland China, Hong Kong and Malaysia, along with India and Vietnam. According to recent Census data, by 2021 the majority language spoken at home in Box Hill was Mandarin Chinese or Putonghua (33.9%) ahead of English (32.5%).

This image from the 1960s shows East Asians introducing their foods to the earlier arrivees. Today, the majority language of homes in Box Hill is Mandarin Chinese.

This fairly recent influx of new residents has, within a generation, not only reworked the city demographically but also in developmental terms. A huge, bustling shopping complex with countless Chinese-influenced outlets now sits on top of the completely rebuilt, exceptionally busy, Box Hill suburban railway station. High-rise buildings dot the landscape all around this rail-tram-bus and shopping hub today – including the 36 storey “Sky One”, which is the tallest building outside the CBD. And more are on the way. Compared to the Box Hill where I first came to work over 50 years ago, it is simply unrecognizable.

Box Hill today. Image: HappyWaldo CC BY-SA 4.0

Unsurprisingly, in view of the demographics, Box Hill has been given a name in Chinese. It has been transliterated – in Putonghua-Pinyin – as: Bo Shi Shan. The first two pinyin words sound somewhat like Box and Shan indicates Hill in Chinese. When translated (literally) back into English, however, this designation becomes “PhD or Doctorate Hill”. An auspicious name attractive to new residents and local real estate agents, alike.

Box Hill now radiates an unmistakable vitality. It is distinctly more energized today than so many other suburbs across this city of 5 million people. It is also true that a number of long-term, local Box Hill residents find all this change unsettling, saddening and sometimes jarring. The city they knew 30-40 years ago is no longer there.

CONCLUSION

China has created a huge civilization. One which naturally contains widely differing points of view. But it is also a civilization which is characterized by a remarkable level of high understanding about what priorities apply in order to secure optimal societal organization.

Professor Allinson, formerly based at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, observed, over 30 years ago, that:

One has to genuinely search very hard to find any Western analogue to this [Confucian] emphasis upon family relations as the originating source of ethical values. … If my general theory of at-homeness is correct, then, for the Chinese mind, the family represents a natural extension of oneself. There is no need to prove the priority of the family.”

Various important values proceed from the operating structure of the Chinese family. These include: a stress on self-reliance and self-help (within the family unit); the clearest understanding of the value of hard work; a powerful respect for and commitment to betterment through education (especially for all new generations); a focus on the acquisition of material wealth (within the family) as a hedge against bad fortune; and a clear understanding of the value of thrift. These factors have understandably shaped the Chinese migration experience across many generations.

Over the 200 years plus during which the modern Chinese Diaspora has materialized, China has endured: an extended period of humiliation at the hands of European and Japanese colonizers; the overthrow of the millennial, Chinese Imperial System; an egregiously brutal war waged in China by Japan; and an intense Civil War which culminated in the creation of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949. Prior to the open-door policy established by 1978, further destructive turmoil unfolded during the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution.

Since 1978, however, total GDP in China has risen around 80-fold from US$218 billion to some US$18 trillion. The PRC has lifted over 800 million people out of extreme poverty since 1981 according to the World Bank. China alone was responsible for 75% of total world poverty reduction over the period from 1981 to 2010. In less than 20 years, it is expected that China’s middle class may grow to be more than double the size of the US middle class. This astounding growth, the fastest sustained expansion by a major economy in history, has generated many positive consequences worldwide.

It is within this remarkable growth experience that the BRI has been incubated – prior to being applied globally, since 2013, across the developing world and beyond.

The respected Singaporean diplomat and academic, Professor Kishore Mahbubani, recently concluded that the BRI initiative had been an “outstanding success” by making infrastructure projects happen (with ecological responsibility increasingly stressed) in many different countries, with different cultures and governance systems. China had been generous, he said, noting that infrastructure investment is “one of the best ways to boost economic growth”.

As it happens, when we consider the remarkable long-term consequences of the global pattern of pioneering Chinese migration, we see an advance indication of the potential of the BRI. This macro-migration experience could aptly be described – considering its extended collective impact – as a vast, bottom-up, uncommonly successful, DIY-BRI (Do it Yourself – BRI). The BRI is, today, retracing some exceptional early footsteps.

Richard Cullen is an adjunct law professor at the University of Hong Kong and a popular writer on current affairs.

Image at the top shows a Chinese-American, image from 1890 to 1920, Library of Congress.