Critics say that it has become harder to become a District Councillor in Hong Kong.

But that was precisely the point. When we look at the dramatic change in the council’s activities in recent years, the alterations make sense, say some observers.

Nevertheless, the recent legal challenge to the revisions was problematic, as it blurred the gap between politics and law in the city, says top legal commentator Henry Litton.

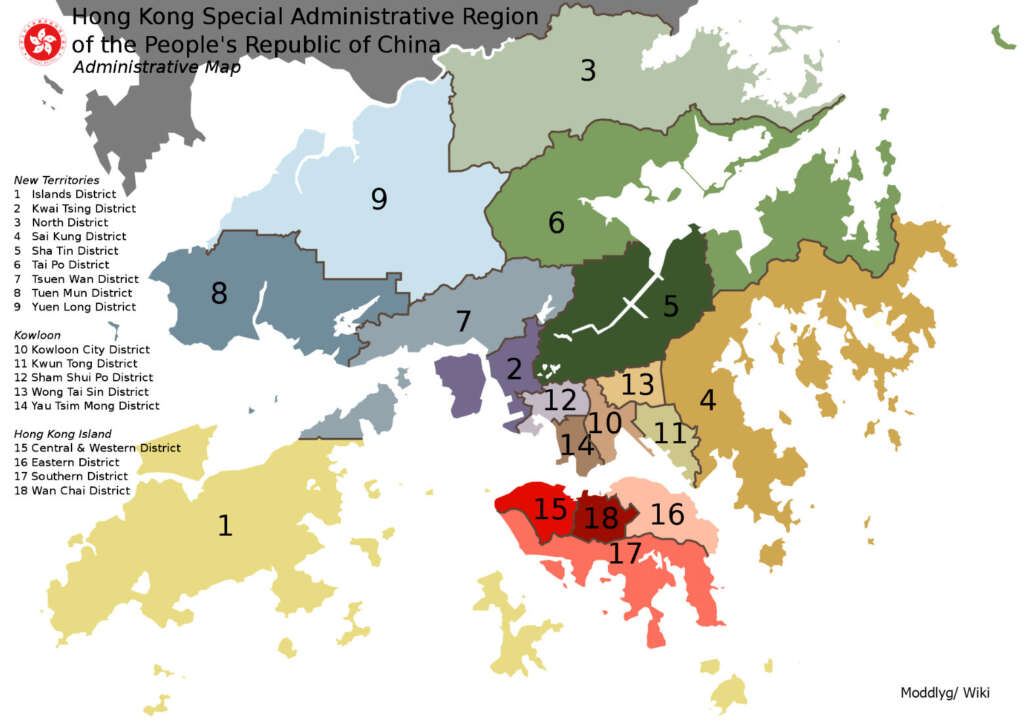

FOR THE PURPOSES of local grassroots administration, Hong Kong is divided into 18 Districts, each with its District Council.

Alongside the Councils, there have been committees set up from time to time, to advise the government on specific issues of local concern. For present purposes, there are three committees, whose members were all appointed by the Secretary for Home and Youth Affairs: the District Fight Crime Committee, the District Fire Safety Committee and the Area Committee.

Following the mass resignation of Councillors in 2020, these three committees took on greater roles.

From about the time of the Occupy Central movement in 2014 onwards, District Councils became progressively dysfunctional, engaging more and more in political activities well beyond their mandate. As Mr Chik, Principal Assistant Secretary for Constitutional and Mainland Affairs puts it: in the course of the District Councils’ last term “there were deviations from [their] major role during the black-clad violence where they had become highly politicised and their normal advisory function has been lost”.

This led to the government undertaking major structural reform of the Councils, commencing with public consultation in May 2023. The time-table was tight. On 10 July 2023, after extensive debate in LegCo, the amendments to the District Councils Ordinance, Cap 547, took place, giving effect to the reforms.

The new Councils will have 470 members, divided into three classes in the ratio 4:4:2. Regarding the 20% segment, the members will take their seats through universal suffrage in their respective geographical constituencies.

The franchise is regulated by a new section 5A and section 7(2)(b) of the District Councils ( Subscribers and Election Deposit for Nomination ) Regulation, Cap 547A . In particular, the regulations stipulate as follows: anyone seeking nomination as a candidate must obtain endorsement from ( i ) not less than 50 and not more than 100 registered electors in the constituency and ( ii ) not less than 3 but not more than 6 members of each of the three committees.

Previously, anyone so minded could rock up to a constituency and, with no more than 10 endorsements from registered electors, put himself or herself forward as a candidate. He or she might be totally unknown in the district and have no connection with the people living and working there.

MORE DIFFICULT

As can be seen, the new nomination regulations make it significantly more difficult for someone from the outside to stand for election as a District Councillor. This, just as plainly, is the very object of the reform: to ensure, where possible, that candidates should have local connections and might, for instance, have already participated in some form of district social, cultural or sporting activities, and be known in the district. This, rightly or wrongly, was considered by the government to lessen the chance of the new Councillors engaging in destructive activity, and give greater prospect of their adherence to the overriding principle of patriots governing Hong Kong.

But this led to a “constitutional” challenge, on the basis that the nomination regulations breached Articles in the Basic Law and the Hong Kong Bill of Rights.

On 6 November 2023 Kwok Cheuk Kin (dubbed Judicial Review King by the media) lodged Form 86 in the High Court seeking leave to challenge the “constitutionality” of the nomination regulations: Kwok Cheuk Kin v Chief Executive in Council, Secretary for Justice & Secretary for Constitutional and Mainland Affairs [HCAL 1978/2023]. Kwok was then acting in person. The matter was dealt with by Coleman J who eventually delivered a 74-page judgment.

It appears from the steps taken by the judge that, from the start, he was minded to give relief to the applicant; for instead of dealing with the matter ex parte as required by the rules, he immediately gave what he called “tight time-table directions to bring this matter to a rolled-up hearing”: that is to say, to call upon the putative respondents to come forward and show cause why leave should not be given to Kwok to commence judicial review proceedings and be granted relief. The judge showed his leanings by his mystic first sentence where he said:

“Henry Ford is supposed to have said, ‘You can choose any colour you like- so long as it is black’. It may be suggested that, whilst firmly disagreeing about the colour, the HKSAR Government approves of the underlying sentiment as to choice”.

The judge was obviously referring to the “choice” afforded to citizens in a District Council election under the new regime but, in his view, given those regulations, it was in reality no choice: they would not get nominated: rather like Henry Ford cynically giving “choice” regarding colour to buyers of his cars.

When it became apparent that the judge thought there was merit in the application, Kwok was given legal aid.

His challenge was based on (a) Article 26 of the Basic Law and (b) Article 21 of the Hong Kong Bill of Rights. As there was no suggestion that applying those two provisions might lead to different results, it would be convenient to focus simply on the challenge under the Basic Law.

Article 26 of the Basic Law reads as follows:

“Permanent residents of the Hong Kong SAR shall have the right to vote and the right to stand for election in accordance with law”.

This goes together with two other provisions as follows:

“Article 97: District organisations which are not organs of political power may be established in the Hong Kong SAR, to be consulted by the government of the Region on district administration or other affairs, or to be responsible for providing services in such fields as culture, recreation and environmental sanitation.

Article 98: The powers and functions of the district organisations and the method of their formation shall be prescribed by law”.

It is difficult to see how the Basic Law was engaged in this case.

As regards the new nomination requirements, they were “prescribed” by LegCo exercising normal functions.

And in relation to Article 26, the “right to vote and to stand for election” was untouched. All that can be said is that the new regulations made it more difficult for some people to stand for election.

WHERE WAS THE BREACH?

How then could it be suggested that the nomination regulations were in breach of the Basic Law?

Is one to interpret Article 26 as conferring on an aspiring candidate a personal right to demand that there be no conditions, no restraints attached to his or her application to be registered as a candidate? If that were the case, then the old regulation – requiring endorsement by at least 10 registered electors – was also unconstitutional. But if that was lawful, how then is the requirement of endorsement by 50 registered electors unlawful? Is it, then, a matter of numbers? And who decides those numbers? The Judiciary?

And what makes the requirement of endorsement by at least three members of each of the three committees unlawful?

The judge was in fundamental error when he concluded that Kwok had an arguable case for relief.

After the putative respondents had filed evidence in response to Kwok’s case the judge proceeded to an inter partes hearing, involving argument by counsel on both sides. This took place on 30 November. It posited the possibility, of course, that Kwok might win. Otherwise the whole exercise would have been a total farce.

Assume, on conclusion of the inter partes hearing, that Kwok did win, and the judge had given him relief, declaring the nomination regulations unlawful. What then?

To start with, given the tight time-table, the polling date 10 December would have to be scrapped and, with it, the commencement date for the new regime (1 January 2024) postponed. But what then was the government to do thereafter? To revert to the old nomination rule? Or to devise new rules to the judge’s liking? How would the government know what that might be?

As can be seen, the judge had stepped well outside his judicial role; he had in reality assumed legislative powers. Never mind that LegCo had thoroughly debated the issues before the amendments became law. For the judge that was not good enough. He had, in effect, constituted himself a one-man upper chamber of parliament. Additionally, there were three threshold reasons to debar Kwok from getting leave to proceed.

One:

As the judge said: “I think the standing of the Applicant [to bring the proceedings] is at best doubtful”: para 117. This refers to s.21K(3) of the High Court Ordinance which requires an applicant to have “sufficient interest in the matter to which the application relates”. Kwok had no interest above that of anyone else. He claimed however that his application was “representative of the public interest”; as to which the judge said “…..the Applicant should not be regarded as having a sufficient interest merely because of the strong merits of the proposed challenge”: para 112(4).

Two:

The application went first before the judge ex parte, as required by the rules where, for obvious reasons, an applicant had a duty of full and frank disclosure. As to this the judge said: “It is of particular concern that the Applicant has been less than full and frank in light of the warning given by me in a previous case where the Applicant was also applicant: Kwok Cheuk Kin v Secretary for Health [ 2022 ] 5 HKLRD 348 at para 156-159”.

Three:

Order 53 r. 4(1) of the High Court Rules requires that an application for leave should be “made promptly and in any event within three months from the date when grounds for the application first arose unless the Court considers that there is good reason for extending the period within which the application shall be made”.

As to this the judge said that the three-month period “is merely a long-stop period – or a quantified default time limit”. The primary requirement is that the application must be made “promptly”.

Here the amended Ordinance was gazetted on 10 July 2023. On 24 July the government announced the polling date to be 10 December. Kwok did not lodge his application until 6 November: most certainly not “prompt”, and not even within the “long-stop period” of three months.

Added to Kwok’s difficulties was this: as the judge said, he deliberately delayed. This was because he “chose the ‘wait-and-see’ approach, to see what would in fact happen during or as a result of the process involving the Nomination Requirement”: para 131. Then the judge added:” Adopting a ‘wait-and-see’ approach has been consistently discouraged by the Courts. In most circumstances, the Court will not instinctively favour with an indulgence any applicant who has deliberately delayed making an application”: para 132.

MIASMA OF CONTRADICTIONS

How, in these circumstances, could Kwok possibly have obtained leave from the judge to proceed to seek relief?

The answer seems to lie in para 138 of the judgment where the judge said that “the merits come into play when considering both aspects of standing and what should be the consequences of undue delay”.

In brief, he considered the merits “strong” and they provided “good reason” for extending the time, even though there had been undue delay: para 135. And here the judgment enters into cloud cuckoo land. After very many paragraphs, the judge “drawing together the strands” reached this conclusion:

“The application for leave to apply for judicial review is granted, with the necessary extension of time for so doing, because it appears to me – and should be evident from the lengthy discussion above – that the intended application for judicial review was reasonably arguable and had a realistic prospect of success.

However, the substantive application for judicial review is dismissed upon full consideration of the merit”: paras 216-7.

What is one to make of all this – assuming one had the time and energy to plough through 74 pages of the judgment?

According to the judge, Kwok had a strong case on the merits, and a “realistic prospect of success” – but not strong enough, realistic enough.

In this miasma of contradictions, the law dissolves into a cloud of words. Its vigour and discipline is lost. All one needs to do is to raise the cry of “unconstitutionality” for the court to go plunging forward in pursuit of justice.

No wonder the human rights industry is flourishing in Hong Kong.

The Honorable Henry Litton was Permanent Judge of the Court of Final Appeal in Hong Kong from 1997 to 2000.