The western mainstream media’s brutally negative narrative about Hong Kong has spontaneously caused the emergence of a range of voices energized to stand up and speak out for the community, says Richard Cullen.

AFTER ENCOUNTERING a fresh set of unvaried, China-thumping articles in the New York Times, I sometimes wonder if others, like me, mentally tweak its famous masthead slogan to read: “All the News That’s Fit to Twist”.

The focus of this article is writing in English about Hong Kong (and mainland China). First, though, it may be helpful to explain some discussion-guiding perspectives.

WESTERN FRAMING-DEVICE

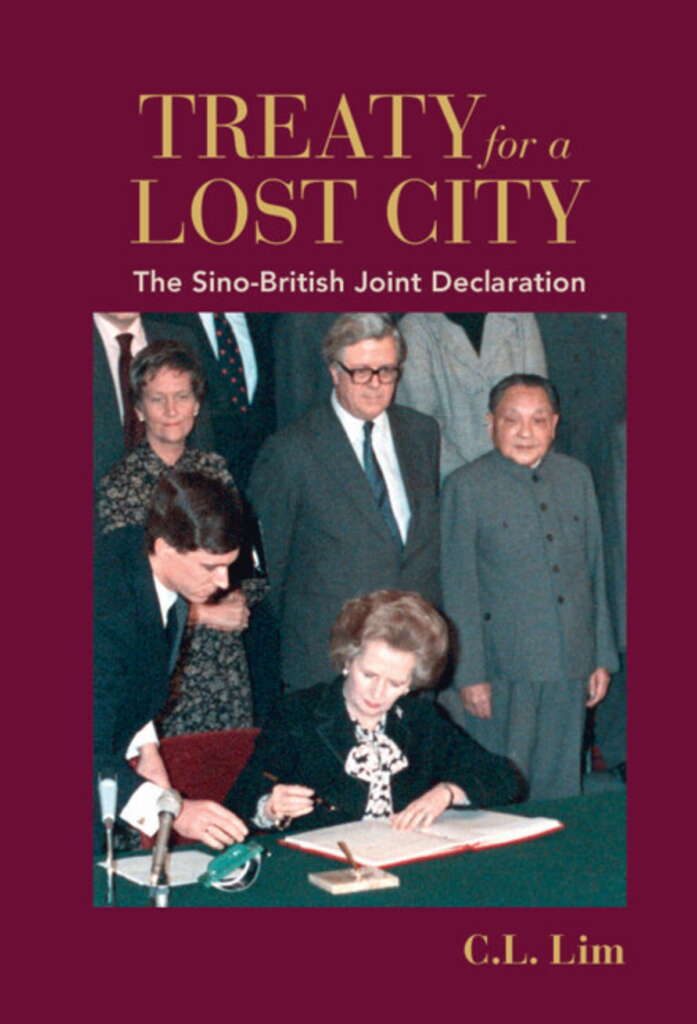

A recently published book on the Joint Declaration by Professor Chin Leng Lim at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, highlights a dominant, Western framing-device for understanding the rest of the world. It long predates the “rules-based international order” of which we read much today. By the 19th century it came to be known as the European Law of Nations (ELN). It divided the world up into civilized (that is, European) nations and uncivilized nations and “the enslavement, for that is what colonialism was” could, based on this fundamental viewpoint, then be justified under international law.

There was also a semi-civilized category: un-Christian but “not considered entirely barbarous” within the ELN, which included China, Siam and Japan together with the Ottoman Empire.

This noteworthy western way of looking at the world still casts a recognizable shadow today, evidenced, inter alia, by the “rules-based order”. Speaking of which, the way that this “order” has been reshaped by the US into a brazenly self-serving, encircling device is neatly précised in this astringent summary carried recently by Fridayeveryday (see this article).

More than 120 years after this cartoon (in Puck magazine, 1902) was published, the western mainstream media still sees western ways of governance, representation, moderation, and so on, as inherently superior. Image: Library of Congress.

There were, however, other Western views. The gifted Belgian-Australian Sinologist, Simon Leys, in a superb book, The Burning Forest (1988), put it this way:

It is only when we contemplate China that we can become exactly aware of our own identity and that we begin to perceive which part of our heritage truly pertains to universal humanity, and which part merely reflects Indo-European idiosyncrasies.

I first read this passage over 30 years ago. I found, from that first reading, that it began to shape my reflections on Hong Kong and East Asia, quite vividly. It has continued to do so.

Leys, in fact, was a scathing but exceptionally well-informed critic of the Communist Party of China (and especially the Cultural Revolution). Which, in a way, added further gravitas to this position on China just stated. He also spotlighted, indirectly yet clearly, how self-serving and narrow-minded the worldview offered by the ELN was, notwithstanding its colossal, martially-backed impact.

MY ARRIVAL IN HONG KONG

I first arrived in Hong Kong to work at the law school at the new City Polytechnic of Hong Kong in late 1991. Within a year I was writing regularly about what was still British Hong Kong including an extended article on the public revenue regime, whose remarkable development dates back to the very start of the colonial era.

In an aircraft over Kai Tak Airport. Image by Christian Hanuise/ Wikimedia Commons.

I have been writing about Hong Kong – and mainland China – ever since. However, my writing has been freshly energized over the last several years. I have also noticed how I am not alone in this regard. More on this shortly.

But I would like firstly to relate certain facets of my own energizing-journey.

Over a decade ago, I began to worry more about elements of Hong Kong’s political development, when – notwithstanding arguments to the contrary by the Pan-Democrat movement – I argued that the political high ground in Hong Kong had become a vacant lot. My fears of how harmful this development was for the HKSAR were confirmed as the Occupy Central Movement unfolded in 2014.

The movement was hugely disruptive – and costly – for Hong Kong and these aspects were profoundly aggravated by the protracted disregard shown by its organizers for the rights, well-being and convenience of millions of Hong Kong residents.

Occupy Central, 2014. Image by Ken Ohyama/ Wikimedia Commons.

SELF-CLAIMED RIGHTEOUSNESS

Virtually all the mainstream western media – and many Hong Kong media outlets – needed little persuasion to support the self-claimed righteousness of the occupy cause. I was one of those not persuaded, and argued in one article that media-leaders of the offshore occupy central cheer squad, like the BBC and Guardian, would have been seething with indignation if protesters had shut down access across all the primary arteries in London for even a few days – let alone three months.

In far off Hong Kong, however, sizeable numbers, persuaded by their own hallowed Western-tilted beliefs, were set on crippling the day-to-day operation of the city in the name of advancing their version of true-democracy. The western mainstream media swiftly recognized an add-oil opportunity. This sort of thrilling militant virtue was just the shot to teach the HKSAR a lesson about the limits of its post-colonial autonomy.

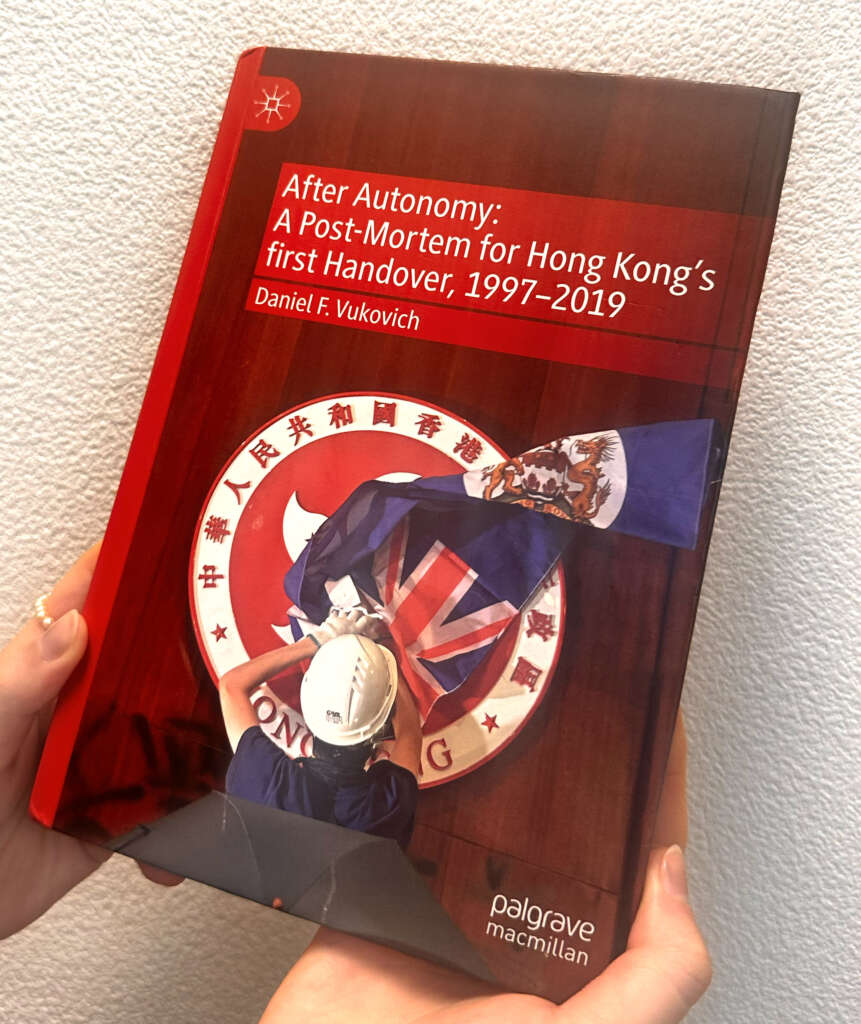

These (and later) developments are comprehensively explored, as it happens, in a new book by Daniel Vukovich, described by one reviewer as: “[A] blistering critique of Hong Kong’s troubled decolonization since 1997”.

The mainstream western coverage, at that time, largely slipped into go-with-the-occupy-movement mode. Slack reporting was common, too often sauced with some active distortion. The worst was yet to come, in 2019, of course. By 2014, however, I could feel, first hand, the immense mendacious power of what John Menadue has called: “[The] White Man’s Media in which the hegemony of the UK and particularly the US is entrenched.”

After the disorder created by the occupy central movement came the 2016 overnight riot in Mong Kok. At least then, The Economist (for example) said that this was the worst rioting seen in Hong Kong in some 50 years. But how the mainstream western media tune changed in 2019.

The former Hong Kong, Court of Final Appeal judge, Henry Litton, cogently summed up what Hong Kong experienced starting in mid-2019: “What Hong Kong faced was an insurgency, the overthrow of the government, nothing less”. The repair bills for businesses, public facilities, universities and shopping malls, for example, were simply colossal.

Billions of dollars worth of shops and transport facilities were wrecked in more than 100 attacks of violence and arson — now all whitewashed by the western media as “pro-democracy protests”. Image: Fridayeveryday

VIOLENT INSURRECTION BECOMES ‘PRO-DEMOCRACY DEMONSTRATION’

The mainstream western media, almost as one, swiftly called the one-day attack on the Capitol in Washington in January 2021, an insurrection. Yet, ever since, they have continued to label the extended, intensely destructive period which brought Hong Kong almost to its knees in 2019, as “pro-democracy demonstrations“.

Believe it or not, within 24 hours of the January 6 Insurrection in Washington, one leading US online publication argued that it was impermissible to compare these two shocking manifestations of political violence.

Police in Hong Kong were blamed for the violence, and foreign elements airbrushed away, making noble heroes of people, some of whom were making bombs using the same explosives as in the infamous “London 7/7” bombings. Image: Studio Incendo/ Wikimedia Commons.

This sort of selective, narrative-lane-switching when writing about Hong Kong and China is now simply habitual within the mainstream western media, never mind any contradictions.

Thus:

Oh no! Zero-Covid is very bad public policy and must be stopped!

China stops its Zero-Covid policy.

Oh no! China has stopped its Zero-Covid policy: this is surely bound to lead to fresh Sino-havoc!

SCHRODINGER’S CHINA

The coming-and-going example which may take the biscuit, though, is the way that, all at the same time: China is a glowering threat to the rest of the world (that is: a challenge to American hegemony); and China is (yet again) on the verge of a grave economic collapse.

Cartoon by Luo Jie/ China Daily

The reader may not be surprised to learn that a series of Western commentators have squared this circle by arguing that it is when an Empire is in decline, that it is most dangerous. There may well be cogency in this argument but, in 2023, it is not China, but the US which provides five-alarm confirmation of the validity of any such claim. And it has been doing this insistently for well over five years.

Unsurprisingly, I have found myself recurrently wondering, what on earth is going on?

THE RISE OF HONG KONG’S DEFENDERS

And so, it transpires, have many other attentive and expressive observers who have deep roots in Hong Kong. They, too, have been galvanized by the persistence of this immensely dominant mainstream western media bent on doing Hong Kong – and China – as much harm as they can through their outlets. (Meanwhile, Western governments championing the “rules-based order” in semi-sacred terms are predictably delighted.)

Many of these observers are now working to push back against this great tide of tilted, media-tosh directed at belittling Hong Kong and China. Just some of those are prominent writers like Grenville Cross, Regina Ip, Henry Litton, Alex Lo, Christine Loh, and Daniel Vukovich. Plus Nury Vittachi, whose ground-breaking book on the 2019 insurrection, The Other Side of the Story, injected a remarkable jolt of vivid good sense into the discussion.

Alternative outlets have helped greatly, too, including Fridayeveryday. And the China Daily has played a pivotal role by providing a traditional (local and global) platform for wide-ranging views.

Then there is the Australian online journal, Pearls and Irritations, started some years ago by John Menadue (aptly described by Robert Manne as “one of post-war Australia’s most distinguished servants of the public good”). By 2021, John Menadue was actively encouraging a range of writers to tell the other side of the story on the HKSAR and China.

SPONTANEOUS MATERIALIZATION

What is truly striking, is the way this responsive upsurge materialized spontaneously – without any prior organization. Although the excellent coordination work of Hong Kong-based journalist Albert Lin has been invaluable in facilitating later republication and translation of many articles, people initially found their own purpose – and their own need to write – individually.

All these writers have differing views, of course. There is no coach or captain of this “team”. But Hong Kong has brought them together. A deep love of the city and a concern about its future are the primary bonds – energized by a shared desire to respond to the dismal, unrelenting flow of mainstream western media disparagement. The hectoring (sometime hilarious) criticism and the harping, arrogant lectures are, in their way, a gift that keeps on giving: a continuous energizing tonic that fires up the desire to write.

‘WEST-KNOWS-BEST’ LEGACY

Those in the mainstream western media maintaining this vast, judgmental stream of Sino-negative commentary regularly bring much energy and creative skill to their project, of course. Their discussion-modes, however, are almost always ultimately framed by that West-knows-best, ELN legacy. Instinctively, most share a high-minded view of the “rules-based order” and how vital it is to stand up for this American stipulated, global governance regime.

They also remind one of Noam Chomsky’s response to an interview question from Andrew Marr, on the BBC, in 1996: “I don’t say you’re self-censoring. I’m sure you believe everything you’re saying; but what I am saying is that if you believed something different, you wouldn’t be sitting where you are sitting.”

There’s no organizing body for the voices standing up for Hong Kong: they simply share a deep love of the city and a concern for its future. Image: Jimmy Chan/ Pexels

Much earlier, in the 1930s, Upton Sinclair concluded that: “It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends on his not understanding it.”

George Orwell wrote a superb essay, in 1946, entitled, Why I Write. He concluded by aptly observing that: “All writers are vain, selfish and lazy, and at the very bottom of their motives lies a mystery”. Reminding us, finally, that: “[It was] invariably when I lacked a political purpose that I wrote lifeless books and was betrayed into purple passages, sentences without meaning, decorative adjectives and humbug generally.”

Richard Cullen is an adjunct law professor at the University of Hong Kong and a popular writer on current affairs.

Image at the top by fridayeveryday.