Hong Konger Richard Cullen re-visits Edinburgh and sees proof of a fact that is now well known: capitalism, for all its benefits, brings significant problems too. We can’t yet know whether America’s or China’s systems will solve them. Meanwhile, historic Edinburgh today has joyful tourist parties at its heart but poverty around the edges.

The London Review of Books recently carried a perceptive article by Rory Scothorne entitled: “Edinburgh’s Festivalisation” (click here to read it).

The article begins by noting how Scotland’s initial settlers, who arrived around 14,000 years ago, must have first pitched their tents in summer, as “nobody in their right mind would choose to live here during the winter”, continuing that, even as far south as Edinburgh, the winter sun is gone by 4 pm while: “the rain eats umbrellas for breakfast and the Artic gale is as rough as sandpaper”.

Reading this prompted a vivid recollection of my own initial visit to Edinburgh almost 50 years ago. I had driven there from London, with an overnight stop in Bradford, as I began my first ever trip to the UK. It was September. The weather had been comparatively mild, but Edinburgh was an entirely new experience – unrelenting, fierce wind-driven rain enveloped the entire city.

I had to find an umbrella swiftly. It did not take long to locate a hawker willing to assist me – at a premium price. As it happens, this high-priced, folding brolly turned out to be an excellent purchase. It coped splendidly with whatever Edinburgh could throw at it and I used it for at least another 15 years after I returned to Australia.

HISTORIC EDINBURGH

Despite the climate, Edinburgh, with a population of just over half a million (smaller than Macau) is, simply, a beautiful historic city. It is a place that people love to visit.

It lies on the Firth of Forth estuary with the Pentland Hills to the south. The Castle Rock (a large volcanic plug) towers over the city and on it sits the remarkable Edinburgh Castle (a castle has been on the rock since the 11th century). The area was known to the Romans when they occupied Britain (from 43 AD to 410 AD). Various local and nearby Kingdoms maintained control in the early Middle Ages after which the Royal Burgh (or borough) was founded by King David 1 in the 12th century. English control emerged during the 14th century by which time Edinburgh was being described as the capital of Scotland. More warfare ensued, but Edinburgh continued to develop.

Elizabeth 1 of England, after a long reign, died childless. Which meant that King James VI of Scotland stepped out of Edinburgh Castle to succeed to the English throne, in 1603, as King James I of England. The Stuart (originally spelled Stewart) Dynasty thus created a personal Royal Union of England and Scotland. The 17th century, dominated by the Stuarts, was especially turbulent, leading to Civil War, the execution of King Charles I, Cromwellian rule, restoration and, finally, the forced departure of King James II (England’s last Roman Catholic monarch) to France in 1688, during the Glorious Revolution.

By 1707 the two Kingdoms were formally joined by Acts of Union to become the single Kingdom of Great Britain. Edinburgh remained the nominal, administrative capital of Scotland – but it was no longer a separate, Royal Capital. Yet more warfare unfolded as Bonnie Prince Charlie (the “Young Pretender”) grandson of James II, tried, unsuccessfully, to retake the crowns of Scotland and England for his father (the “Old Pretender”) in 1745. This uprising was comprehensively and brutally putdown, in 1746, at the Battle of Culloden.

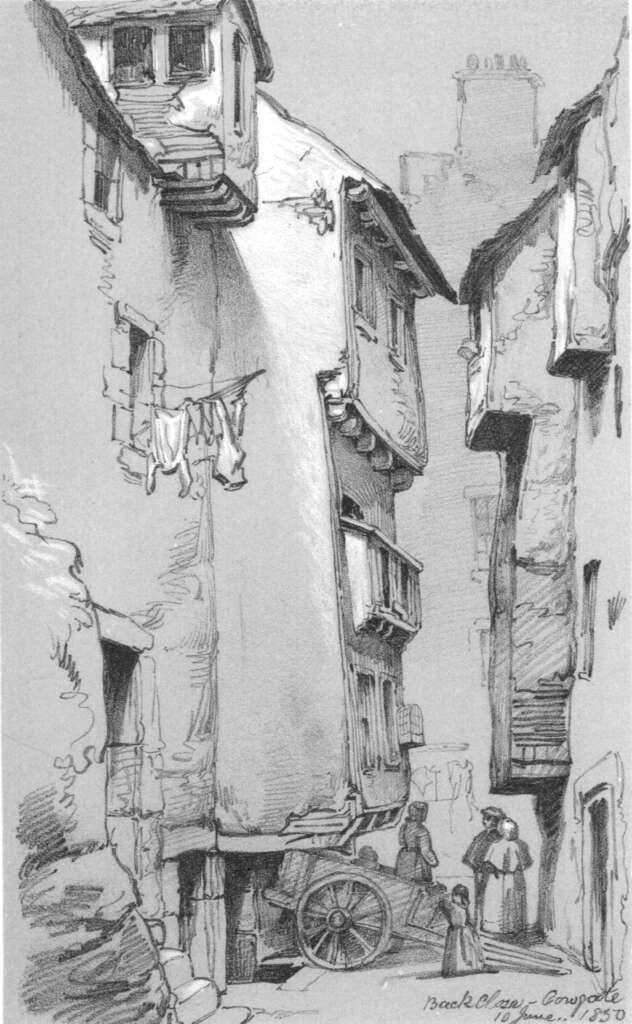

By the mid-18th century, the original Old Town of Edinburgh had become notorious for unsanitary overcrowding. The construction of an extensive, Georgian, New Town, based on a grid-system of streets, was built between 1767 and 1850. This was also the time of the Scottish Enlightenment and renowned figures like David Hume and Adam Smith.

MODERN EDINBURGH

Work to remedy the grave ills of the Old Town began in the mid-19th century. In the 1960s, major, controversial public projects did still more to reverse the enduring decay in the Old Town. Edinburgh, meanwhile, rebuilt and retained its place at the second most important financial and administrative centre in the UK after London.

In 1998, under a devolution programme initiated by the British (Blair) Government, Scotland regained its own Parliament – for the first time in almost 300 years – which was re-established in Edinburgh.

FESTIVE EDINBURGH

Scothorne notes, in his article, how the Scottish Reformation “stamped out idolatrous Yuletide celebrations and Christmas only became a public holiday in 1958”. Edinburgh, had, however, begun celebrating the New Year (Hogmanay – the Scots word for the last day of the old year) in the Old Town, by the 17th century. By the late 20th century, this New Year’s Eve party had grown hugely, with over 400,000 people attending in 1995.

But this was now only a part of the growing festive calendar. Edinburgh played host to: the Royal Edinburgh Military Tattoo; the Edinburgh International Festival; the far larger Fringe Festival; The Edinburgh Jazz and Blues Festival – plus: a Science Festival, an Art Festival, a Children’s Festival and a Book Festival. There is even, now, a Christmas Festival. Much of this still growing macro-tourist-Edinburgh is privately and commercially energized.

Long gone is the joyless reputation of a city soul, “Bible-black [in colour] pickled in boredom by centuries of sermons”. The rapid influx of international capital pushing all that bleakness aside is, however. producing “homogenization or worse, Disneyfication”. Meanwhile, 5,000 Edinburgh households “face nightly homelessness”.

The Global Financial Crisis (GFC), triggered by extraordinary loose lending in America – camouflaged with even more extraordinary debt-shifting financial instruments – caused massive economic disruption around the globe for several years from 2007-2008. Scotland had long been home to certain highly regarded financial institutions including: the Bank of Scotland (which, through a merger, became HBOS in 2001) and the Royal Bank of Scotland. Both these Scottish financial icons were laid low by the GFC, striking gravely at Edinburgh’s standing as a financial centre. This loss, indirectly, added more impetus to Edinburgh’s embrace of hyper-tourism.

Another recent diagnostic article by Mike Small in The National (Scotland) argues that: “Edinburgh’s tourism has turned it into a derelict theme park”.

He explains that a new tourist tax – a visitor levy applied to accommodation – is envisaged, as the Edinburgh Council struggles to make ends meet. It may close a range of public sports and other facilities across the city in working class communities to reduce expenditure, according to this report. Meanwhile, Small says, “the tourism industry has fleeced people for decades” as the entire city has been “turned into a theme park.” And the city leader is supporting the new levy “to help the city fund its festivals.”

Small concludes by observing that the idea of the tourist tax being diverted into the hands of the tourism industry is absurd, arguing forcefully that:

“It would mean the capital had effectively been captured completely and any effort to halt or slow the process utterly defeated. There would now be a closed loop of cash circulating through the hands of a rentier class and a handful of businesses and organisations while the rest of the city’s residents service that industry or languish in the periphery. Edinburgh is a city of great storytelling and literature but that is a grim ending for any story – and one that is a disgrace if it is allowed to be written.”

CONCLUSION

Edinburgh has been the pivot of an exceptional amount of political and economic history within Great Britain over many centuries. It has witnessed great turbulence plus significant triumphs and defeats. It is a much-admired city that has, over this very long period, found the capacity within itself to recover and prosper repeatedly.

These recent critical reviews, however, argue that the present framework-for-thriving is entrenching major, publicly shaped and funded benefits for private tourism (and related) elites at the expense of the wider, general population.

Modern political philosophers give the term, the social contract, a particular meaning: an unwritten agreement regarding rights and responsibilities shared between a jurisdiction and its residents. It is a term dating back to the 17th century work of Thomas Hobbes. Its scope was made more explicit in the 18th century by John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Briefly, it describes the circumscribed but protective and usually mutually accepted forms of interaction among individuals and groups within their governing environment. According to these recent critical reviews, the social contract in Edinburgh has been progressively and clearly tilted in favour of certain private elites.

Another way of confirming that this may be so is suggested by an extended commentary, from about a year ago, where Professor Yuen Yuen Ang, from Johns Hopkins University, was interviewed. In this New York Times article – which was focused on the geopolitical contest between America and China – Professor Ang argued that, what matters is: “[W]which of these two countries are going to make use of their political system to solve the problems of capitalism?” The critics above might argue, if they referred to this general test, that Edinburgh, today is compounding rather than solving those problems of capitalism.

Richard Cullen is an adjunct law professor at the University of Hong Kong and a popular writer on current affairs.

Photo at the top by Roan Lavery on Unsplash.