The average Chinese person lives in a small city you’ve never heard of – and that’s where you begin to gain a deeper understanding of the people and the country.

FOR FOUR DAYS, I’ve been in southern Hunan in the city of Chenzhou (郴州). Chenzhou is not a big or famous city. But its stories are worth telling anyway. I’ll tell you why.

Let me start with a framing question:

Where do you suppose most Chinese people live? Big cities? Small cities? Villages?

I was curious, and honestly didn’t know the answer. To find out, I looked up the population of all 19 First Tier and New First Tier cities in China, and added them up. The sum was 293 million people, which is just 20.7% of the total Chinese population.

In other words, eight out of ten Chinese people don’t live in the 19 biggest cities.

So where do they live? The answer: In…

- 30 Second Tier cities (places which the average non-Chinese living in China will have heard of, but perhaps not visited.)

- 70 Third Tier cities: (The average Chinese person will know most of these. Non-Chinese will likely know only a few.)

- 90 Fourth Tier cities: (The average Chinese person will know only a few of these.)

- 128 Fifth Tier cities: (The average Chinese person will probably ask you: “Is that a city?”

China’s total urbanized population has been estimated to be about 914 million. Subtracting the population of the First and Second Tier cities, that leaves around 600 million urbanized population living in these smaller cities (plus about 500 million more in the REAL countryside). So, in fact, the “median Chinese citizen”, if such a person exists, across 1.4 billion people, should statistically be a resident of a small, mostly-unknown city.

HERE ARE ‘THE MASSES’

And that brings us back to Fourth Tier Chenzhou, in southern Hunan province. Officially it has 4.5 million people, but like many prefecture-level cities in China, that figure can be misleading. Chenzhou has many administrative districts and counties, some of which are far from the city center and could hardly be considered part of the Chenzhou downtown urban build-up. The two core urbanized districts (Beihu District and Suxian District) of Chenzhou have about one million people together.

In my opinion, if you work in any of kind of China-adjacent field and ever reference “the Chinese masses” when you discuss any kind of sociocultural phenomena, or the political priorities of Chinese leaders, you MUST be sure to think about Chenzhou and cities like it. Because that’s where most of the Chinese masses actually live.

NEW MALLS

In Chenzou, people here invariably describe their city as poor and slow-paced (and, in comparison to First and Second Tier cities, they are). But even here, there are new shopping malls, clean roads, nice tea shops, universities, well-manicured parks, and plazas.

I practice a habit that I’ve picked up from traveling with Chinese people: everywhere I go I ask the locals about the price of local real estate. “Our wages… they aren’t high. Actually, house prices… they aren’t high either. But they’re still expensive for sure, because of our low wages,” says my cab driver. “Chenzhou is poor you know. We aren’t wealthy like Changsha,” he adds, referring to the provincial capital of Hunan.

CHECKING HOUSE PRICES

I fact-check using some real estate apps. New Chenzhou real estate averages 5,000 to 7,000 RMB/sqm. Nicer places cost 10,000 RMB/sqm. The fanciest, newest luxury apartment building in town is 21,000 RMB/sqm. This is just ONE FIFTH the price you’ll pay for an old construction, secondhand apartment in Shanghai.

“This machine is broken. The machine on the first floor is broken too. We have to go to the second floor. The hospital is too poor,” the nurse at the Chenzhou First People’s Hospital tells me, as I try to scan my barcode to pick up the results of my 16 RMB PCR test.

“It’s good you speak Chinese,” she adds. “No one here speaks English. Last year we had a foreigner here for a test, it was very difficult to communicate.” Hmm, so they get one per year?

I figure there are probably less than 15 non-Chinese living in this whole city. I wonder what paths they took to get here? Searching on LinkedIn, I find one woman supposedly teaching English here. Has she really been here eight years?

DINNER IN A MALL

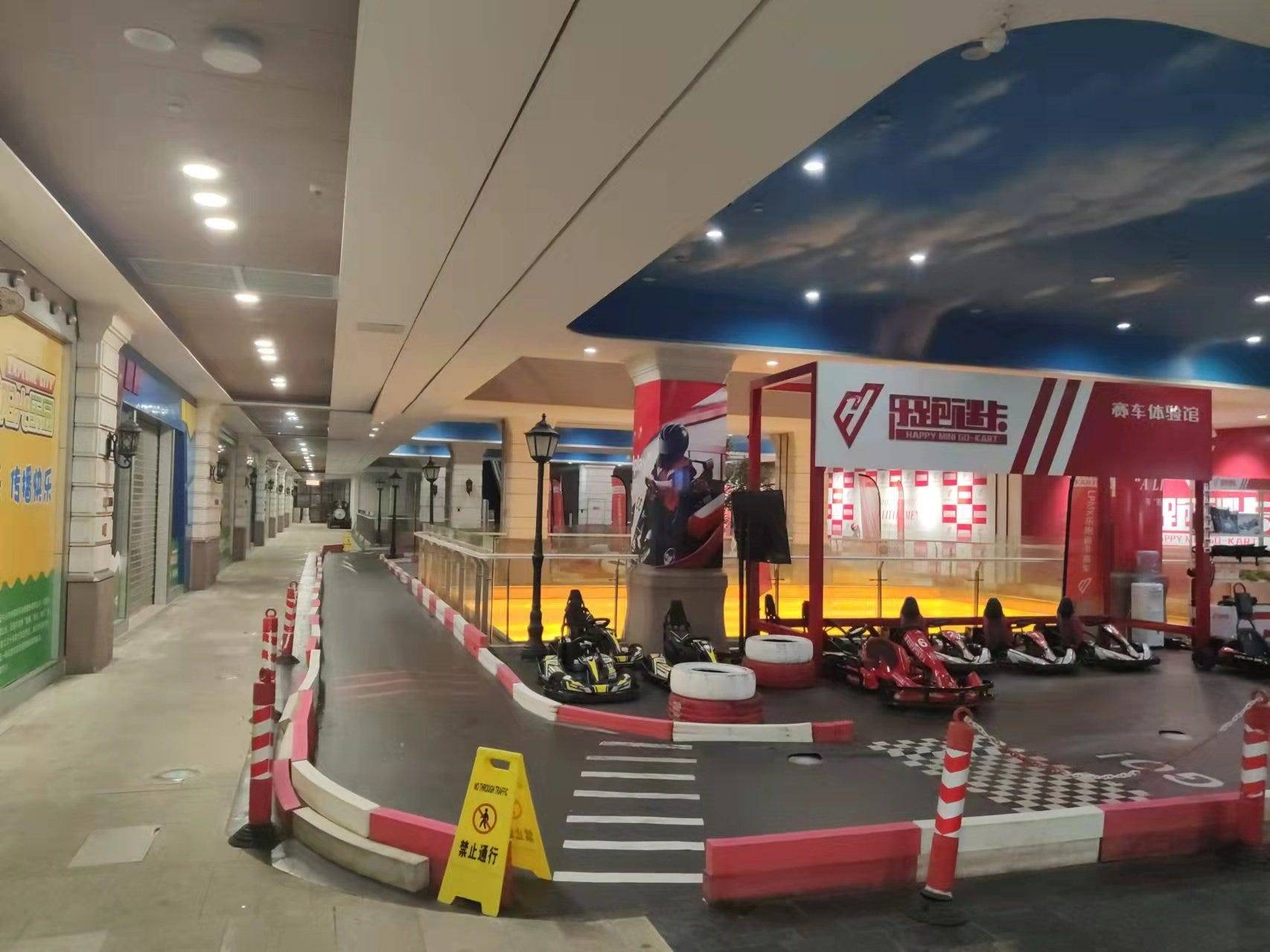

My wife and I go out for dinner that night in a nice, newer-looking mall. The Korean BBQ restaurant has touchscreen ordering. The mall has a trampoline park and a go-kart track and a ball pit.

“It’s so much more fun to be a kid now in China,” says my wife. She grew up in the 1990s in a Hubei city even smaller than Chenzhou. “There’s so much more to do. “

The mall, the nicest in town, has an H&M, a Uniqlo, and a bevy of domestic brands I’ve never seen in malls in any large cities. There’s a wall of street food waiting outside the main entrance. No Starbucks, but there is a Pacific Coffee, the Hong Kong copy of Starbucks. There’s no Louis Vuitton or Gucci; If you can afford those, you have to go to Changsha.

STOLEN TRADEMARKS

Out on the pedestrian street near the mall, the ancient tradition of not giving a fig about registered trademarks is still practiced loudly and proudly, unlike in the big cities. I guess small cities are now the sweet spot for these knock-off products.

Domestic brands aren’t safe either. This local “ode” to a certain famous Changsha tea chain has 26 locations in Chenzhou, according to online reviewing platform Dazhong Dianping. One review says: “The style of 霓裳茶舞 looks similar to SexyTea… isn’t it TOO similar?”

This is the logo of the tea brand in question – a well-known Changsha-based milk tea chain with locations in dozens of cities. Take a close look at the logos and draw your own conclusions (oh, and the menus are identical, too).

AND THE NOISE!

The streets of Chenzhou are an overwhelming cacophony of car horns, recorded messages screaming about shop discounts, and wizened chain-smoking uncles dragging up a half-century of tar from their lungs every five seconds. It smells of stinky tofu and motorcycle exhaust and the air has a humidity level of 95%.

But everyone is intensely friendly. Everywhere I go, a chorus of “Hello! How are you!” and “外国人!” [“Foreigner!”] follows. People stare openly until you stare back (except kids; they keep staring).

To my surprise, I hear mostly Mandarin in Chenzhou, even from adults. Only old folks are speaking Hunanese. But, if you’ll allow me to offer a subjective statement here: of all the regions I’ve traveled to in China, Hunanese efforts to speak Mandarin (i.e. 湖普) yield some of the most labored, garbled results I’ve EVER heard. Ethnic minorities in remote villages in Guangxi speak clearer Mandarin than the locals of Hunan. It feels like there’s some fundamental linguistic incompatibility between Hunanese and Mandarin going on here. But I digress.

TWO SPECIAL THINGS ABOUT CHENZHOU

Chenzhou itself is only known for a few things:

1) Having a funny name.

郴 chēn is a very rare character that only appears in this city’s name. It means “a town in a forest” (林中之邑).

2. A few natural scenic areas that are “Hunan famous” but not quite “China famous”.

An example of this: About 30km north of downtown is the new tourist town of Zixing: population 320,000, administratively part of Chenzhou, but quite different.

A REAL DESTINATION

In 2015, the provincial government got the local Dongjiang Lake upgraded to a 5A tourist attraction. Now Zixing is on its way to becoming a Real Destination. That’s why we’re here.

The receptionist at our guesthouse is a local. She says all the new guesthouses and restaurants on the river are owned by Changsha bosses, including this one.

She thinks the tourism has been good for the river: it’s better maintained and prettier now. But it’s also louder now, with lots of construction. One gripe she has: the new restaurants opened by Changsha bosses are too expensive. They charge the same prices for locals as they do to tourists, which isn’t very nice.

She makes just 2,000 RMB (US$300) plus meals and housing a month, but it’s better than going to work 12 hours a day at the electronics factory. At the factory, she could get 3,000 to 4,000, but it’s harder work. Having a tourism industry is a nicer way to stay in her hometown. Otherwise, you must leave, like most of her classmates. One went to Changsha and came back after a month. Missed home. The receptionist says she has never been. Went to Shenzhen once though. Didn’t like it… too big.

STEREOTYPED CHARACTERS

At this time, I am intensely thankful for the privilege of being able to travel and work at the same time, exploring this country, filling in bits of knowledge like a paint-by-numbers. The countryside, the small cities, the big cities, all part of the patchwork of the modern Chinese existence.

Too often, I think the conception of the modern Chinese citizen is reduced to a limited cast of stereotyped characters visible in First Tier cities: The tech worker. The artist. The migrant worker. But there’s a whole different cast of humanity in smaller cities, people who can’t be conceived of if you’re only seeing samples of large cities.

Like my receptionist, the small town local who doesn’t want to move to the big city, away from her family, but who also doesn’t want to work in a factory, and is delighted that tourism created a job that lets her sit in an air-conditioned lobby and watch videos on her phone. Hah!

“I WOULD LIKE TO SHARE”

Today I had a really nice chat with one of the cleaners at the hotel, Mrs. Xu. I was asking some questions of a different receptionist and she didn’t know how to answer, but Mrs. Xu overheard. And she was very happy to talk.

Basically, I was asking the receptionist what living conditions in Zixing were like before the 5A tourist rating in 2015 and she was saying: “Sorry, I’m 18 years old… I was a child.”

And then Mrs. Xu (a star, honestly) was like: “I WOULD LIKE TO SHARE NOW” and then talked nonstop for almost an hour.

So. Mrs. Xu was actually born in the “库区” i.e. “reservoir zone” and moved down from the mountain into Zixing city when she was five years old. “Reservoir zone” is what the old locals call Dongjiang Lake, because before it was rebranded as a tourist lake, it was just a reservoir.

The dam where the lake feeds into the river was planned back in the 1960s but was halted and didn’t end up being completed until 1986 (image below).

HARD YEARS

The years between 1986 and 1989 were very hard for the local villages. There was originally no lake here, so the damming of the river flooded their fields and they starved. That’s when Mrs. Xu came down to Zixing City: it was too hard to live in the “reservoir area” as the lake was still forming.

I grabbed this aerial shot of the dam (above) from dongjianghu.com. It faces south, with the dam/lake to the east, and the river slicing northwest down through the canyon. On the tourist bus coming in (the road is visible on the canyon wall), the guide introduced the dam, including Dongjiang Lake’s role as a clean water reservoir and the dam’s role as a peaking power station for the Central Grid.

THE SILKWORMS DIED

Mrs. Xu said that the gov’t tried to help the flooded village economies by introducing new industries. First, they tried silkworm cultivation, but those didn’t take very well. The silkworms all died, and the villages stayed poor.

Then researchers from a state-owned fruit company came and said the climate was good for fruit. Fishing in the new reservoir and fruit cultivation became the new industries.

At first the fruit sold poorly because it wasn’t known around the country as a place for fruit, but then the government arranged large state-owned fruit companies to buy the fruit produced and sell it in the coastal provinces, so now their output is guaranteed. I had a local plum (above) at breakfast one morning. It was a bit too sour, but I think it’s still too early in the season.

TRIP TO THE LAKE

When you arrive inside the tourist zone, next to the dam, you have the option of taking a hike of about an hour through the Dragon Vista Canyon or a boat ride out to the island and back. The canyon path is a really nice little hike. Fairly steep, but that means fewer people. The dam is visible in the first picture.

After my enjoyable hike, I was ready for the other attraction at Dongjiang Lake: the boat ride out to the island in the middle of the lake.

But my experience was about to go downhill.

This is a good time to talk about one of the worst things about traveling to famous attractions in China: package tour groups. On our boat ride, we had the severe misfortune of sharing the ferry with a tour group of middle-aged women out on a tour group and MY GOD they were loud.

My head was ringing after five minutes. Douyin videos, ringtones, shouting into cell phones held at arm’s length, all punctuated by barks from the guide’s microphone. It was claustrophobic and actually anxiety-inducing. It’s worth planning your whole trip around avoiding tour groups. I couldn’t believe how much sound they were generating, in glaring contrast to the serene, natural surroundings.

NEED FOR NOISE

But actually, bizarrely bad sound-related experiences are common in Chinese tourist zones. Earlier, while hiking the canyon, enveloped in the musty smell of earth and water, and the buzz of frogs and cicadas, I rounded a bend and found a speaker concealed as a stump, blaring a bassy electronic song with a whiny high-pitched children’s chorus. Why would you do such a thing?!?

Some of this can be attributed to cultural differences. There’s an important Chinese word renao 热闹 that means like… bustling, active, full of energy. Certain places are supposed to be 热闹, like restaurants, plazas, shopping centers. That’s why you see restaurants designed as one giant room. People don’t want a quiet dining area.

But I find this craving for 热闹 goes too far for my tastes. I don’t want my nature trail to be 热闹. I don’t need a misty riverfront to be 热闹. And the 热闹 that a group of excited middle-aged aunties on vacation brings to the party is ALWAYS too much. It’s deafening.

The lake itself is… pretty nice. Halfway through the boat ride, you can go to the upper deck and take pictures. There are small villages on the banks with fruit orchards, clearly the beneficiaries of the state fruit-buying campaign.

ESCAPING THE AUNTIES

We arrive on the island and run ahead of the tour group to try to make it to the cave. We were hoping to get in ahead of them, but no such luck. They do the tours in batches, and they ended up waiting for the tour group. We say screw it, skipping the cave and taking the next boat back to the mainland to escape them.

Mrs. Xu says the cave on the island is natural and she remembers visiting it as a kid. You used to have to take a flashlight in and it was scary. When the tourist area was built, they expanded the cave and installed lights. I’m not so concerned about missing it. I’ve been to a lot of caves in China. They’re fun, but they tend to all look the same, something like this (see image).

MIST ON THE RIVER

On the way back, we catch a few glimpses of the mist on the river. In places where the canyon narrows, the mist on top of the river piles up like chunky clouds, lasting later into the day because the canyon walls prevent the sun from burning it off.

Mrs. Xu says the area got famous a decade ago because a photographer from Beijing stayed here for a year and took pictures of the fishermen in the mist. The local fisherman casting their nets into the misty waters is the quintessential Dongjiang Lake shot. I didn’t get one myself, so this picture (below) is also from the internet.

THE PHOTOGRAPHER

I check up on the details of this story, which of course is totally accurate, because Mrs. Xu is the best.

The photographer’s name is Cao Guangwen and his photography basically created Dongjiang Lake as a travel destination back in the first half of the 2010s.

But here’s the funny thing: the fishing doesn’t happen here anymore. Mrs. Xu says those guys throwing nets into the water for tourists to take pictures is a staged performance. The local government doesn’t want fishing boats driving around and polluting the water.

Mrs. Xu doesn’t know where the supposed “local fish” on all the restaurant menus come from. Not Dongjiang Lake though.

Fortunately, my taxi driver on the way back to Chenzhou train station knows: These days, the fish are cultivated on fish farms in the river downstream from the tourist area. In particular the “Dongjiang Salmon”.

Yes, that’s right, salmon. Zixing is famous for its salmon sashimi!

WHY PEOPLE ARE SHORT

I mention to Mrs. Xu something I’ve noticed: Many people in this area are REALLY short, especially elders. She’s quite short herself. Sometimes you’ll see three generations of the family walking together and the tallest person in the group will be a 12-year old girl.

She answers with a big smile: “That’s because children eat well now!” She continues with the same smile, oblivious to the unsettling contrast with the words she’s speaking: “When I was young, it wasn’t that we ate poorly… it was that there was nothing to eat at all.”

But, she adds, thanks to tourism and fruit cultivation, replacing fishing, (which was forbidden in 2015), the villages of the “reservoir area” are now some of the wealthiest in Zixing. Villagers grow fruit and also can rent their properties to entrepreneurs who open guesthouses. These economic activities have proven to be quite profitable.

POVERTY ALLEVIATION

I do some research online and find a story describing how this arrangement was used in Bailang Village, which is apparently the last village in the area qualified for poverty alleviation.

As part of the poverty-alleviation program, a Mrs. He was able to rent out her home to a guesthouse operator for 80,000 RMB per year, including an up-front payment of 200,000. She always collects a wage by working in the guesthouse.

At this time, I am struck strongly by the complexity and depth needed if you want to faithfully and honestly tell the story of the Chinese economic transformation.

Rarely, if ever do you find a story that is clearly black or white, success or failure, an easy framing for a lazy summary report. It’s a story of gradual improvement, picking out a path by trial and error. In these meandering, tricky journeys, there are surely lessons to learn for other developing countries though.

There’s an ancient Chinese maxim that explains it clearly. “You can cross a river by feeling for the stones underfoot.”

Enjoy the journey.

Image at the top by Yikou645/ Wikimedia Commons