Yes, the west IS addicted to war. We may think that all nations or regions have a similar propensity to conflict – think of China’s “warring states” period. But when we consider history, we find that the global west actually has a significantly higher propensity to take up arms against whoever it wants to. Richard Cullen takes us through a brief historical overview of warfare around the world.

HISTORY CONFIRMS THAT the present, destructive militaristic culture of the US-led Atlantic alliance stands on the shoulders of well over a thousand years of Western immersion in extraordinary levels of horrific warfare.

Introduction:

In June 2021, the leading Singaporean international affairs commentator (and former President of the UN Security Council) Kishore Mahbubani published a short, robust paper which stressed that: “The Pacific has no need of the destructive militaristic culture of the Atlantic alliance”. This is surely right.

However, it is valuable to consider: the roots of that destructive militaristic culture; why they are so deep-seated; and why this war-tilted culture is still profoundly influential across the “Global West” – a useful shorthand term explained in the Financial Times, around two years ago, in this way:

“In its efforts to win what President Joe Biden calls a “contest for the future of our world” with China, the US is increasingly looking to an international network of allies, which can loosely be called the “Global West”. Like the Global South, the Global West is defined more by ideas than actual geography. The members are rich liberal democracies with strong security ties to the US. Alongside the traditional western allies in Europe and North America sit Indo-Pacific nations such as Japan and Australia.”

The Global Footprint of Modern Warfare

Presently, two terrible wars are raging within the primary geographic-sphere of the Global West, with no end in sight: in Ukraine and across the Israeli-created hellscape in Gaza (which is spilling over into the West Bank and regionally).

Earlier, in the 20th century, Europe brought us World War I, from 1914-1918 – the War to End All Wars. That war did not secure this outcome. World War II followed from 1939 – 1945.

WWII was also intensely fought in East Asia, South-East Asia and in the Pacific, it is true and that horrific conflagration was triggered by Japan. However, Japan was governed, according to Encyclopaedia Brittanica, from 1192 to 1867 by an “hereditary military dictatorship” known as the Shogunate.

And when Japan modernized after 1867, that martial influence endured. Unsurprisingly, Japan’s subsequent invade-and-conquer empire-building closely emulated the militarized, European imperial-colonial prototype.

The reasons for these shocking repetitive outbreaks of massive levels of warfare are complex. But the fact remains that it is within the historical Global West that the most extensive and destructive modern wars have been incubated and then triggered.

Next, consider the battle data since WWII.

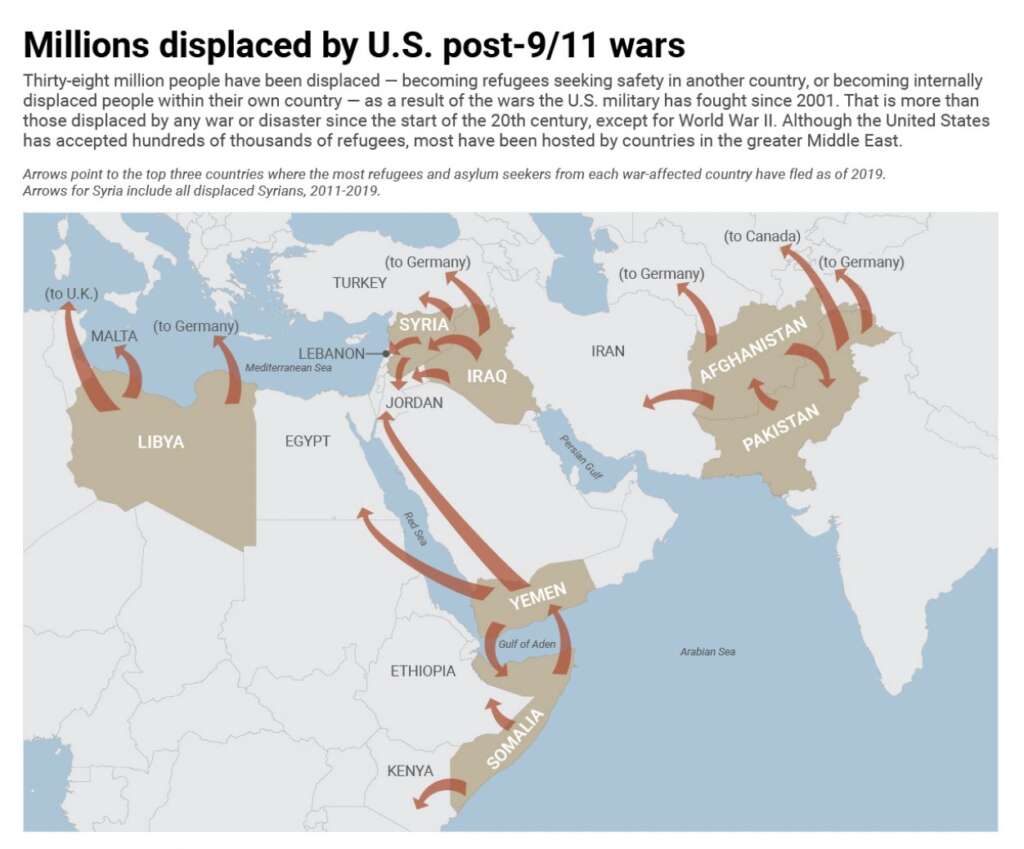

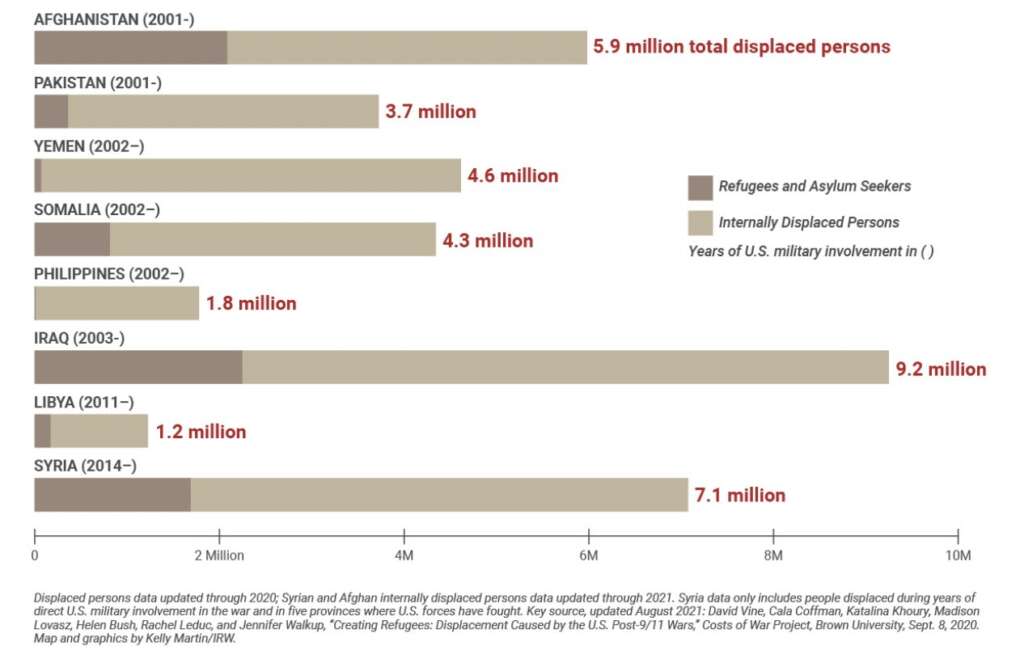

An American, Brown University study claims that, following the 911 attacks in 2001, the US (relying on its 750+ worldwide military bases and multi-trillion-dollar expenditure) has caused: “4.5 million deaths and displaced 38-60 million people” (click here for link).

In the period since WWII the US, along with its satellite-allies, has been involved in an extraordinary number of wars – apart from fomenting repeated offshore uprisings and coups. According to Xinhua: “Incomplete statistics showed that from the end of World War II to 2001, among the 248 armed conflicts that occurred in 153 regions of the world, 201 were initiated by the United States.”

Thus, looking back around 100 years, one is confronted by a shocking catalogue of colossal violence and destruction, anchored predominantly in the Western world. What is most striking, though, is how gruesomely repetitive it is. Again and again, the wealthiest Western countries have contributed to the formation of the destructive militaristic culture noted at the outset.

So how might this be explained? As it happens, there is a useful comparative profile – based on a short review of certain pivotal turning points in Chinese history – on which we can draw to help answer this question.

Warfare and Statecraft in China

The “Warring States” period in China ran for over 200 years, from 475 BC to 221 BC as the Zhou Dynasty entered into decline. During this time “seven or more small feuding Chinese kingdoms” were engaged in repeated warfare until the State of Qin triumphed and established the first Chinese Empire in 221 BC. The short-lived Qin Dynasty (221 BC – 207 BC) was replaced by the far more durable Han Dynasty (207 BC – 220 AD) by which time, “many of the governance systems and cultural patterns which were to characterize the next 2,000 years were established”.

The First Emperor of China is remembered, according to Professor Franz Michael, as:

“[A]n infamous tyrant and oppressor, a destroyer of old cultural values who burned the books, killed the scholars, and afflicted the people with forced labour for his massive public works”.

But Qin Shi Huang is also remembered as a great unifier who changed China politically, socially, economically and intellectually in ways which laid very long-term foundations. Weights and measures were standardized, roads were built, coinage was systematized at the same time as the remaining feudal estates were broken up. China established a centralized, bureaucratic form of imperial government, which displaced previous Zhou-Feudal governance systems.

Most importantly, the system of writing, using characters, was standardized relying on the Qin mode of writing these characters. The new Chinese Empire was thus established by deploying a uniform system of writing which could be applied across the entire empire. This was particularly significant in China because the system for writing, using separate characters to record all aspects of life (including people, things, concepts and actions) stood largely apart from the differing, spoken languages. Unlike Europe’s once universal written language, Latin, this was not an alphabet-based writing system where the spoken word is converted to writing by using code-symbols to represent spoken sounds.

The essentially secular Confucian ideological scheme, which has so shaped China at both macro and micro levels, originally emerged during the early Warring States period as the Zhou Dynasty began its long decline. This scheme (which was to prove more durable than any other political-social-economic method of State-organization, anywhere) stipulated a moral system, to which the Emperor had to adhere if he were to retain the Mandate of Heaven. Moreover, it preset a remarkable (especially compared to Europe) formal hierarchy of social classifications, in descending (summarized) order of merit, namely: scholars; peasants; craftsmen; merchants; and soldiers.

Warfare and Statecraft in the West

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire was preceded by the Roman Kingdom (753 BC – 509 BC) and the Roman Republic (509 BC – 27BC). The very powerful Roman Empire, established in 27 BC, was later split (by 395 AD) into Eastern and Western components. The Western Roman Empire endured until 476 AD, outlasting the contemporary Han Dynasty in China by over 200 years.

At its height, between the 1st and 2nd Centuries AD, the Roman Empire circled the Mediterranean Sea and extended well beyond (for example to Britain). It covered around 6.5 million square kilometres and had a population between 50-90 million. It was highly organized, politically sophisticated and heavily militarized. It relied, economically, on extensive use of slave-labour. As in Ancient Greece, battle-hardened warrior performance was conspicuously well regarded, with numerous generals rising to very high political office, including Julius Caesar.

European Feudalism

After the collapse of the control applied by Western Roman Empire, fragmented European Feudalism steadily filled this political space. Meanwhile, before and after that fall, powerful tribes invaded by land from the North. Vikings later did likewise by sea. Within much of Europe, numerous kingdoms were recurrently engaged in gruesome conflict with one another. The Islamic invasion of Europe from the East had also begun by the 8th century leading to frequent confrontational responses, including the Crusades.

Repetitive local and regional wars were thus very common. Such conflicts came to be dominated by cavalry. To sustain the many feudal armies required substantial grazing lands for the horses. A notable feature of this decentralized, war-focused agrarian political-economic scheme was the comparatively limited productivity of the separated, Middle Ages, agricultural economies.

Meanwhile, this post-Rome, fragmented, war-scarred European experience was not brought under any meaningful new centralized control by Charlemagne’s Holy Roman Empire (sometimes referred to as the First Reich). As Voltaire noted, this agglomeration was neither holy, nor Roman, nor an empire.

European Transformation

The European Renaissance, began to unfold in the 14th century as the European Middle (or Dark) Ages drew to a close. This movement generated, amongst other remarkable changes, a massive uplift in the European study and understanding of statecraft (the means by which societies can be better organized and sustained and better protected). As the understanding of effective statecraft developed the emerging stronger States were able to expand and hold territory.

Substantial increases in the comprehension of war-technology followed as did superior understanding of the technology of long-distance sea voyaging. The Age of European Discovery (energized by imperial-colonizing and Christian-religious ambitions) commenced in the early 15th Century led by the Portuguese. Others followed, including the Spanish, the Dutch and the English.

Then came the Protestant Reformation in the 16th century. Widely seen as starting in 1517, with the written work of Martin Luther and others, the Reformation produced a massive schism within the previously unified and overwhelmingly dominant (and seriously corrupt) Roman Catholic Church. The appalling warfare which arose directly from profound ideological splits and conflicts generated by the Reformation surpassed all previous wartime horrors in Europe.

A great deal of this disputation was set down in printed-writing by the warring parties – following the introduction of Gutenberg’s European printing press in 1454 – thus amplifying already deep divisions.

The “Thirty Years War” which ran from 1618 to 1648 is still widely regarded as arguably the most destructive war, ever, in Europe. Although it finished inconclusively, it commenced as a most violent religious war between Protestants States and Catholics States, arising out of the Reformation. Ultimately, this war led to the signing of a series of famous treaties often referred to collectively at the Treaty of Westphalia, in 1648. This Treaty both ended the terrible Thirty Years War for the mutually exhausted combatants and established the concept of the modern, sovereign, essentially secular, Nation State.

This did not lead to a fundamental lift in peace in the West, however.

Neither, unfortunately, did the European Enlightenment (1685-1815). It did so much, of course, to foster advanced thinking based on rational, ultimately secular and scientific principles. But improved thinking is also of great use to those set on waging war. Plus, the Enlightenment was prominent in helping to incubate the European Industrial Revolution (1760 – 1840) which was foundational in establishing new methods for producing yet more destructive weapons (amongst many other breakthroughs).

Primary, ever more powerful European Nation States, were increasingly in conflict after 1648. Their expanding, globalized, imperial-colonial rivalries, which added to intense local tensions, ensured this outcome. According to one study, France and England (later Britain), fought 41 wars between 1109 and 1815 (including the Hundred Years War) where France won 24 wars, England/Britain won 11 and six were a tie. Both France (in the 19th century) and Germany (in the 20th century) attempted, unsuccessfully but at extreme bloody cost, to invade and conquer Russia – in Germany’s case after first conquering France in 1940. Many more examples could be given.

Entrenching Antagonistic Difference

In 1983, Professor Benedict Anderson, from Cornell University in the US, published a controversial but influential book entitled “Imagined Communities”. Professor Anderson argued that modern, Nation-State communities, especially, have to be “imagined” in the sense that they cannot be built, like communities of old, based on face-to-face contact. Members of an imagined community hold a view of “their” nation-community in their minds, which then informs their connection to that nation-community in a wide variety of ways, for example (in modern times) supporting their nation in the Olympic Games or, more historically, taking up the collective national view as their own when considering another nation, not their own. This typically applied when conflict and – or war – arose between neighbouring States.

For Professor Anderson, “Print Capitalism” has been crucial in creating the modern Nation-State – the paradigm, imagined community. That is, the vast growth of mass communication (and literacy) prompted by the invention and rapid, profitable spread of movable-type printing fostered a swiftly rising sense of belonging to comparatively new, nation-communities.

This impact was greatly amplified by the prompt move towards communicating in print based on the local spoken language – and not the old, dominant, near-universal written language, Latin. Thus, one’s sense of separate identity was now captured, increasingly and powerfully, in writing. A deepening sense of separateness from others – but internal kinship – arose within, for example, England, France, Spain, Portugal, the German States. According to this analysis, these changes also weakened more universalist allegiances previously secured through mass adherence to the Christian religion.

Professor Anderson’s analysis of Imagined Communities assists in illuminating this era of European history. The Treaty of Westphalia signalled the establishment of the modern Nation-State era in Europe. The primary tool (modern printing) to build a sense of belonging, above all, to such a given Nation-State was now available and was put vigorously – and effectively – to work. The idea was that these Nation States were meant to co-exist with one another rather than fight to resolve and establish the dominance of a single State.

Intriguingly, Professor Anderson did not address the emergence of China’s national identity in detail in his book. Others have argued that, in fact, China has for a very long time been a huge Civilizational State, rather than a (European-envisaged) Nation State.

Conclusion

Well over 2000 years ago China experienced a distinct, extended and bloody Warring States period, the recollection of which is deeply etched into the collective historical memory. This has not, however, prevented the regular outbreak of war within China ever since. Indeed, in the modern era, China has experienced a sickening rise in violence and destruction exemplified, for example, by the Opium Wars, the Taiping Rebellion, The Boxer Rebellion, two Japanese invasion wars, a terrible Civil War and the Cultural Revolution.

But each such outbreak has reinforced the fundamental lesson of that early, vividly remembered period of extended, intense bloody conflict: war is to be abhorred, not just in word but in deed. Moreover, China has never been drawn – especially in the modern era – into directing militarized attacks at other states on a scale remotely comparable to that seen across the Global West, despite, incidentally, having a population size (and the wealth and power to go with it) comfortably exceeding the total population found in the West.

In the West, the signing of the Treaty of Westphalia was meant to mark a crucial turning away from a default resort to war amongst Europe’s many distinctly divided states, especially wars based on religious difference. It was hoped, too, that this lesson would be absorbed amongst Europe’s foremost states, each vying to assert themselves as “top nation”.

In fact, it took Europe almost 300 years (of further warfare, above all) until 1945 for a piercing consensus to emerge on the wisdom of that co-existence maxim embodied within the Treaty of Westphalia. The post-war creation of the European Union (designed to put an end to the terrible contest to be top nation) is the principal manifestation of this bloodily-forged agreement.

Unfortunately, the US has never experienced any sort of comparable, penetrating “post-Westphalia” shift in its worldview. Indeed, it emerged from WWII as the top nation globally. And it has gone to extraordinary, war-enhanced lengths, since – especially following its triumph over the USSR in the Cold War – to ensure the indefinite tenure of its global “full spectrum dominance”.

The very large, crucial European segment of the Global West remains measurably fragmented, even within the EU. Despite its bitter post WWII collective understanding, it has allowed its own geopolitical interests and thinking to be appallingly swayed (along with Australia, Canada, Japan and others) by Washington’s continuing, fevered determination to impose its will globally, despite – and because of – America’s gravely endangered, international standing.

Today, this posse of America’s geopolitically anemic allies find themselves standing shoulder to shoulder with the US in the devastating prosecution of terrible Western-incubated wars in Ukraine and Palestine. The former US Secretary of State, Condoleezza Rice, identified a primary factor shaping this ominous posture in a recent extended essay in the journal Foreign Affairs. “Great power DNA”, she said, “is still very much in the American genome”.

In conclusion, this contemporary, offensive, distorting US leadership can authentically be understood as the progeny, in significant part, of centuries of Western warring states history. Caitlin Johnstone – while commenting on the current US election dynamic – lately captured the point to which this abysmal US leadership has brought us (her emphasis):

“That’s why you see candidates arguing not about WHETHER wars should happen, but WHICH wars should happen, and HOW they should occur. It’s why you see them accusing one another of being too weak and dovish on foreign policy instead of attacking each other as reckless warmongers. It’s why you see them arguing over who loves Israel the most and who will send it the most weapons, rather than who will do the most to end Israel’s genocidal atrocities”.

Early this year I argued that:

“Notwithstanding massive intensified marketing by the Mainstream Western Media arguing that the West is forever crusading for freedom, democracy and human rights, once one considers embedded, repetitive performance stretching back decades, the dominant motto guiding ultimate American hegemonic action is: Let’s go to war. China, however, has been living in accordance with a very different motto for over four decades: Let’s go to work.”

The presents a fundamental difficulty for Washington. Former US diplomat and leading international affairs commentator, Chas Freeman, cogently argues that, in China, the US does not primarily face a just a rising military rival. Most of all it faces an economic and technological rival with which it increasingly cannot compete. Moreover, it does not know how to adjust to this profoundly changing geopolitical reality other than to lurch towards still greater militarism combined with a fevered injection of “national security concerns” into an extraordinary range of anti-China policy initiatives.

History visibly explains how all this has come to pass. It also confirms how “the destructive militaristic culture of the Atlantic alliance”, which Professor Mahbubani abhors, stands on the shoulders of an ingrained, Western Warring States experience reaching back well over a thousand years. That dismal culture is today sustained and shaped, above all, by the increasing American embrace of forbidding warfare as a primary means to maintain: its messianic ambitions as a global hegemon.

Richard Cullen is an adjunct law professor at the University of Hong Kong and a popular writer on current affairs.

To see a list of articles he has written for this outlet, click this phrase.

Main image at top by