The last Emperor of the Southern Song was a fleeing young royal family member who lived in the Hong Kong town of Mui Wo on Lantau island. He’s been long forgotten now, but the opening of a new metro station named after a monument to him and his brother has revived interest in his astounding story. Emily Zhou and Nury Vittachi report.

ZHAO BING WAS ON THE RUN. He was four years old, so probably didn’t know he was on the run – but he would have been aware that he and many of his family members and their staff were fleeing in a state of terror from the royal palace in Lin’an, then the capital of Song Dynasty China. The Yuan army, from the fearsome northern kingdom of the Mongols, was invading – and they were famously ruthless and violent.

The family, packed onto horses and carriages, with a long line of soldiers and civil servants, headed towards the southeast as fast as they could.

BACKGROUND: ATTACK FROM THE NORTH

For centuries, the rulers of the central part of China had shifting relationships with kingdoms on the outer edges of their land. Generally, the ruling Emperor’s armies were stronger, and the smaller kingdoms acted as vassal states, paying tribute and taxes.

But in the 1270s, everything changed. A tribe called the Yuan people from the northern area we now know as Mongolia, were fierce fighters and highly skilled in battle. They decided that they were now strong enough to take over the leadership of China by force. They headed down from their northern lands, conquering large parts of Song land as they travelled.

REACHING THE CAPITAL

In 1276, the Yuan army reached the capital of the Southern Song Dynasty, the city of Lin’an (臨安). On the throne at the time as Emperor Gong (宋恭帝), aged five – one of several brothers of the above-mentioned Zhao Bing, who was a year younger.

The young Emperor and his staff were captured, but many ministers and the rest of the royal family, including four-year-old Bing, fled, initially to Jinhua, Zhejiang Province, then to Fujian Province, which borders on the sea.

Zhao Bing had another brother who was about three years older than he was. This boy, named Zhao Shi, was enthroned in Fujian province as the new leader of China on 14 June 1276. He was seven years old.

But the Yuan army kept on coming – and Prime Minister Zhang Shijie (張世傑) commandeered ships and headed further south. The plan was to use the flexibility that ships provided to keep the royal family alive, and enable quick escapes. All they could hope for was to stay one step ahead – and China was a big place. One idea was to sail right down to the southern coast to a cluster of fishing villages there.

SOUTH TO HONG KONG

Eventually the Yuan army had conquered much of the land, and the fleeing Song royals and their defenders sailed to Guangdong, arriving at the cluster of coastal areas and islands that we today call Hong Kong.

Centuries-old records indicate where child Emperor Zhao Shi and his little brother Bing lived while they were here. They appears to have spent some time at a place called Sacred Hill in Kowloon Bay — a mound with an unusual rock on top of it. The two brothers were said to have sheltered in the shadow of the rock, where they could stay under cover and yet see any approaching danger. At one stage, they also appear to have lived in Tuen Mun.

But it appears that they spent much of their time in the seafront town of Mui Wo on the coast of Lantau island.

SHI’S TROUBLED LIFE

They kept the boats nearby, as there were lots of coves on Lantau Island where they could hide.

During one water-borne episode in the waters on the coast of Mui Wo, a massive typhoon hit the area, and the boy Emperor fell off the boat and almost drowned. After he was rescued, a decision was made for his brother and himself to stay away from the water and live in the Mui Wo district. Shi recovered from the shock of nearly drowning, but remained in poor health. His little brother Bing turned five in 1277.

However, Shi seemed to be living an unlucky life. In 1278, he fell ill. Some sources say he died in Mui Wo, while others say he was taken into Guangdong and died in the area that is present day Jiangmen, not far from Shenzhen.

BING BECOMES EMPEROR

His brother Bing, then six, was enthroned in a ceremony in Mui Wo as new Emperor of the Song Dynasty. He was technically ruling all of China from his humble hideout in Lantau Island. But at the same time, it was obvious to many people that power had shifted from the Song leaders to the Yuan people, who were dominating the central part of the country from as early as 1273, and now had control over the vast majority of land, except for a thin strip of the coast of southern China.

Little Bing remained Emperor for more than 300 days, right through his seventh birthday. But in the winter of 1278 to 1279, the Mongols closed in on Lantau Island, and the child and his team moved again.

PATRIOT SOUP

For a while, the child emperor and his entourage hid in a monastery in a city called Chaozhou (潮州), also known as Chiuchow or Teochew. Monks made a leafy vegetable soup for him, to give him strength to rise to one day rule the whole nation again. After he expressed enthusiasm for it, the monks dedicated the dish to him and he named it “Protect the Nation Soup”. The recipe was preserved and the name simplified, in English, to “Patriotic Soup”.

Then Bing and the others returned to Yamen, a bay in Jiangmen, where his brother had passed away, and where supporters lived.

The Yuan army seemed to be unstoppable. The Mongolians eventually reached the Jiangmen area where Shi had died and Bing was hiding.

LAST STAND

The government leaders realized that it was time for a do-or-die last stand.

Prime Minister Zhang Shijie made an extraordinary decision. He ordered about 1,000 ships to be chained together in the waters of the Yamen bay. This would prevent individual ships from fleeing. Everyone had to stay and fight to the death. He had the ships caked with a special fire-resistant mud, to prevent them being set on fire by the enemy.

The Yuan arrived and blockaded the bay, refusing to allow any movement. And then they waited. After a few days, the Song ships ran out of fresh water. The sailors, dying of thirst, drank sea water and became ill.

And that’s when the Yuan attacked.

It is said that the slaughter was so immense that hundreds of dead bodies could be seen scattered over the surface of the waters of Yamen Bay for the following week.

WATCHING FROM SHORE

Meanwhile, Zhao Bing had been kept safe on shore, watching from a vantage point.

When fierce fighting began on the water, he stood with his minder, an old statesmen called Lu Xiufu (below). Bing had reigned as Emperor of China for 313 days, mostly from his Hong Kong home in Lantau.

Old Lu saw what was happening on the water. Defeat was inevitable. This was not just the end of a battle. This would be the end of a great dynasty that had lasted three centuries. The old man could not bear to think of the young child being humiliated or hurt by the invaders.

He picked the boy up and walked right to the edge of the cliff. “The previous emperors have been humiliated a great deal,” Lu said. “Your majesty should not have to bear being humiliated.”

He leapt off the cliff and they both died on the rocks below.

The Mongolians won the war and the Yuan Dynasty ruled the whole of China.

The boy-king Zhao Bing of Mui Wo became known in the historical scrolls of the era as the Last Emperor of the Southern Song.

KEEPING HIS MEMORY

But while there’s an odd antipathy to learning Chinese history among some people in Hong Kong, the tale of Bing and his brothers is not entirely forgotten. Four things keep the memory alive.

First, a small tomb was created for Bing in Shenzhen soon after his death. It was lost and forgotten for centuries, but was rediscovered in the 1960s, and is now maintained as a historical monument by the authorities in Shenzhen.

Second, the leaf soup that the monks had made for him, called Patriotic Soup, is still served today as part of a classic Chinese menu in Chaozhou cuisine.

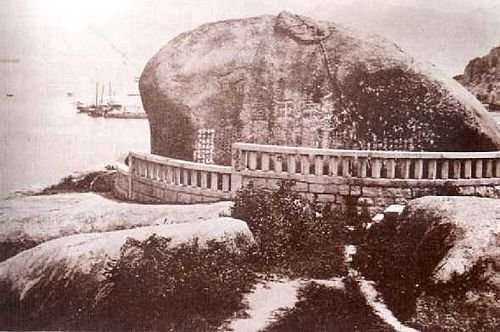

Third, a huge stone on Sacred Hill in Kowloon was carved to remember the boy emperors of Hong Kong. In old maps, the area became known as “Hill of the King of Sung”.

In 1899, Hong Kong people asked the British colonial government to preserve the rock as a historical monument. To their credit, they agreed to recognize it as a historical site. In 1915, a local businessman financed steps and a balustrade so people could climb to the top and visit the site. The area was named Sung Wong Toi, which literally means “Terrace of the Sung Kings”.

But the Japanese took over Hong Kong in 1941. With a stunning disregard for history, they levelled the Sacred Hill and blew up the rock. But the part with the inscription remained intact.

After the Japanese were defeated and removed from the city, the remaining piece of rock was rescued by Hong Kong people. The British rulers agreed to build a garden for the remains of the monument, but chose a spot some 90 meters (300 feet) from its original location.

Today, it doesn’t look particularly impressive, just a slab of rock with an inscription on it in a small park (below). But what a remarkable story lies behind it.

And fourth, a new metro station opened in Hong Kong’s Kowloon City last year. Its name, Sung Wong Toi (宋皇臺) was lifted from that of a historical relic located in that part of the city.

When engineers were digging deep holes for the station and the tracks, they found huge numbers of artifacts, hundreds of years old. To the delight of historians, there was widespread interest. Display cabinets were built by the Arup engineering company so that users of the station could see the items found. They also preserved an ancient well found on the site.

The good news is that the resistance in Hong Kong to learning about history may be more limited than people feared. Many residents are starting to be aware of the remarkable stories that exist, literally, just below the surface of the city.

Image at the top: A Chinese sage with two children on a boat. Gouache by a Chinese artist, ca. 1850. Credit: Wellcome Collection.